http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/iie.18703062e.2013.103.2506

Obras, documentos

450 Years Too Soon: Mixteca-Puebla Style Polychrome Ceramics in El Salvador

450 años demasiado pronto: la cerámica mixteca-Puebla de estilo polícromo en El Salvador

Paúl E. Amaroli B. y Karen Olsen Bruhns

Fundación Nacional de Arqueología De El Salvador

Artículo recibido el 4 de noviembre de 2012.

Devuelto para revisión el 18 de febrero de 2013.

Aceptado el 28 de mayo de 2013.

Resumen

El Posclásico temprano en El Salvador se caracteriza por la fase Cihuatán, una versión local de la cultura de la elite internacional del Posclásico en Mesoamérica. Elementos de esta cultura, adoptada por los salvadoreños, incluyen urbanismo y estilos internacionales, mexicanizados, de arquitectura y de la planeación de centros rituales y de la elite, así como marcados cambios en el decorado de las cerámicas. Entre los nuevos objetos de cerámica se encuentra Banderas polícroma, una versión local de la extendida tradición cerámica conocida como Mixteca-Puebla polícroma. La única muestra excavada por fechar es del mismo Cihuatán y corresponde en su mayoría con el subestilo del códice, un estilo que representa motivos del centro y sur de México cercanamente relacionados con las pinturas de los códices. Estos motivos son, en su mayoría, bélicos. Uno de los más comunes es el chimalli, o escudo, usualmente atado con dardos y atlatls, seguido de cráneos, huesos, partes del cuerpo desmembradas, espinas de maguey y otros artefactos asociados con la guerra y el sacrificio.

Palabras clave: cerámica de estilo polícromo.

Abstract

The Early Postclassic in El Salvador is characterized by the Cihuatán Phase, a local version of the international elite culture of the Postclassic in Mesoamerica. Elements of this elite culture adopted by the Salvadorans include urbanism and international, Mexicanized, styles of architecture and planning of ritual and elite centers, as well as by marked changes in decorated ceramics. Among the new decorated wares is Banderas Polychrome, a local version of the broad ceramic tradition known as Mixteca-Puebla Polychromes. The only excavated sample to date is from Cihuatán itself and is mainly in the Codex Substyle, a style which features motifs of central and southern Mexican origin in a style closely related to codex paintings. These motifs are, in the main, bellicose. The single most common is the chimalli, or shield, usually bundled with darts and atlatls, followed by skulls, bones, dismembered body parts, maguey spines, and other artifacts associated with war and sacrifice.

Keywords: Polychrome Ceramics.

To most "mainstream" Mesoamerican scholars El Salvador is that little known bit of land in the middle of which Paul Kirchhoff drew his line dividing Mesoamerica from what he termed the Chibcha region, now known as the Intermediate Area.1 Given that the amount of modern archaeology done in the country is small and poorly published, even with the re-expansion of the concept of Mesoamerica as covering all of El Salvador plus western Nicaragua and the Nicoya Peninsula of Costa Rica, El Salvador is still not much considered in general studies of Mesoamerican culture. This is unfortunate: western El Salvador was firmly part of southern Mesoamerica from its very inception in the Preclassic, and in later periods its small Maya kingdoms were busily involved in trade, migration, slavery, borrowing and lending with the rest of Mesoamerica as well as with lower Central America. Though cultural traditions in eastern El Salvador are fundamentally different, their affiliation with Mesoamerica was clear in the Late Classic (knowledge of eastern El Salvador remains limited owing to the utter paucity of archaeological investigation in that region). El Salvador's closest Mexican ties, although we do not know the specifics of the interaction, were with the Gulf Coast cultures—this from the Olmec onwards—and with southern Mexico.2 In others words, the Salvadoran Maya acted much the same as other Maya and, in fact, formed a cohesive subgroup within the general Maya realm. With the Late Classic Collapse, the Maya sites of El Salvador also suffered and dynastic elite culture disappeared only to be immediately replaced with what is called the Cihuatán Phase, a superficially Mexicanized Maya culture whose closest ties were with highland Guatemala, the Gulf Coast, and Southern Mexico. The Cihuatán Phase represents the importation of the international/multicultural elite culture seen all over Mesoamerica, a culture which drew heavily upon both central Mexican and lowland Maya antecedents but which cast these elements into a new, highly distinctive, whole.3 The Cihuatán Phase is marked by the appearance of the first urban settlements in El Salvador. The best known of these is Cihuatán itself, although it is not the only urban site of this time period. Las Marías (Pueblo Viejo Las Marías), some 12 km to the Southwest of Cihuatán in an adjoining valley, is also apparently of the same time period, but remains unstudied in any detail, whereas Cihuatán has been known since the 1880s and researched since the 1920s.4

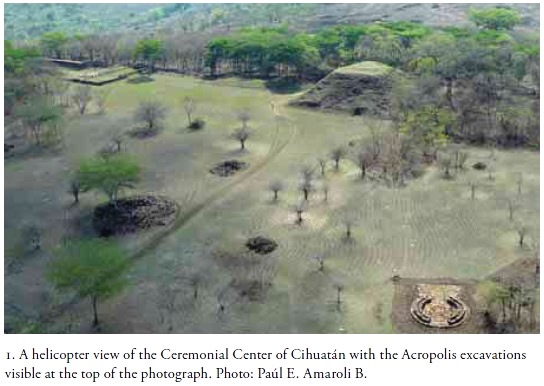

Cihuatán is an immense urban site with a monumental center constructed in the Postclassic International Style (fig. 1). This monumental center consists of a walled ritual precinct which contains two I-shaped ball courts, a large pyramid, and a number of other ceremonial structures, including a round temple related to the cult of Ehécatl-Quetzalcóatl, an adoratorio, a number of other platforms presumably of ritual use, at least three range structures and what appears to have been a multi-roomed building of unknown function to the South of the main pyramid. Separated by a wide plaza, and directly to the East, although on higher ground than the Ceremonial Center, is the Acropolis (fig. 2). Ongoing investigations here have uncovered a series of residential and ritual structures, including a central Mexican tecpan style palace, presumably the living quarters of the rulers of Cihuatán. We do not know who the rulers of Cihuatán were, their origin, or their ethnicity. A possibility is that they were highland Guatemalan or Salvadoran Maya who had absorbed the new elite culture which arose after the Late Postclassic political collapse and were using it to set themselves off from the Classic period rulers. Another possibility is that they were Mexicans who originated in one of the regions strongly affiliated with the new traditions of the Postclassic, as were Puebla and Veracruz. Whoever they may have been it seems very unlikely that they were the ancestors of the historic Pipil, even if the latter were, ultimately, of Mexican origin.5 This new ruling elite seems to have been either very powerful or very persuasive, as they convinced the local population to move into an urban settlement, a type of residential aggregation previously unknown within El Salvador and to embark on an ambitious building program that continued until the final day of Cihuatán.6

Cihuatán, however, is a composite sort of city. Only the monumental center and ritual buildings (which are scattered throughout it, apparently in relation to individual barrios), adhere to pan-Mesoamerican architectural norms. The rest of the city is recognizably Maya in architecture and in the helter-skelter arrangement of household clusters. There is no grid pattern of the sort common in central Mexico and no recognizable streets (a single calzada is known from the contemporary site of Las Marías). That urban settlements were not altogether pleasing to the local population may be indicated by the fact that when Cihuatán was destroyed the entire valley was abandoned until the very end of prehistory when a few very small Pipil settlements were found along its margins by the next group of invaders, the Spanish.

The artifacts of the Cihuatán Phase, especially the ceramics, show considerable continuity from the Classic in domestic wares. However, in decorated wares, especially the polychrome styles, there are radical changes. The Copador and Salua Polychromes that characterized the decorated wares of Classic Salvadoran sites were replaced by a series of local geometric polychrome styles, but also by a local type of Mixteca-Puebla Polychrome with a fully developed, although somewhat limited, iconography which is demonstrably of Mexican derivation. This pottery may have been made by the same people— or their children—who had made Copador and Salua Polychromes, given its similarities in construction and firing. Also the background red slip usually contains specular hematite, a hallmark of "real" Copador. But the style, including shapes, had changed drastically. In place of the plethora of bowls, zoomorphic vessels, and cylindrical vases of Copador and Salua, the Mixteca-Puebla Polychrome from Cihuatán—named Banderas Polychrome by the late Stanley Boggs owing to a common motif: a tri-colored flag—consists of a limited number of forms, mostly individual eating and drinking dishes. To date known Banderas Polychrome vessel forms are flaring bowls with a flat bottom and, often, with tripod supports (locally called huacales) and annular or pedestal based cups with a hemispherical, egg-shaped, or flanged hemispherical bowl. Rare forms are shallow plates and small ollas. All are of a thin, generally cream or beige, paste with a relatively coarse sand temper; all are painted in brilliant colors (white, orange, gray) on a bright red background and bear the remains of a high polish. The only larger form found to date is a large (45cm + diameter) bowl-painted with flags (fig. 3). These larger vessels are known only from a single context and are associated with the area of the royal palace. All Banderas Polychrome vessels—in their decoration, if not their forms—are clearly related to the Mixteca-Puebla Polychrome style of southern Mexico.7

Excavated examples of Banderas Polychrome are known only from Cihuatán, although rare whole examples are known from looting at that site and other Cihuatán Phase sites in western El Salvador. At Cihuatán, Banderas Polychrome is not restricted to elite contexts. Indeed, the only whole vessel we have is from a residential offering, buried in the center of the floor of one house of a plazuela group just to the south of the Acropolis (fig. 4).8 The vessel, the first piece of Banderas Polychrome to be scientifically excavated, contained a small piece of polished jade.

This purely Maya household arrangement was located adjacent to the monumental center. It boasted one higher domestic platform structure and may have been home to a lower elite family, assuming the upper elite lived in the Acropolis palace or adjoining buildings. Sherds of Banderas Polychrome vessels also were found in virtually all domestic structures excavated around the monumental center and Jane Kelley encountered small quantities in her excavations in the San Diegüito Barrio of Cihuatán, presumably a lower middle class neighborhood.9 However, the vast majority ofour excavated sample comes from the Acropolis, from the Palace proper and from the Great Hall complex above the Western Terraces of the Acropolis, where the pieces are found broken, sandwiched in between the burned and fallen roofs and the floor (fig. 5).

Although from looted examples we can delineate several subvarieties of Banderas Polychrome, the Banderas Polychrome vessels from Cihuatán are almost entirely of a single type which we call Banderas Codex.10 These vessels have a highly polished red background with motifs clearly related to, derived from, or ancestral to, those of southern Mexico. Unfortunately, we have only a very small comparative sample of excavated and published Early Postclassic Mixteca-Puebla Polychrome from southern Mexico and it is not very similar. Banderas ceramics, for example, lack the elaborate step fret designs characteristic of the Mexican ware. In fact, Banderas iconography is quite limited and ignores many of the common themes of Cholula, being, in some ways, more central Mexican in content. This immediately raises questions as to how such a developed iconography was introduced, especially since no genuine pieces from southern Mexico have been found within El Salvador. Given the detail evident in many of the motifs, it is quite possible that the specific motifs were introduced through or copied from, paintings on either cloth or paper, that is, lienzos or codices. This means of transmission of complex iconography has been proposed for other cultures of the Americas, specifically for Chavín in highland Peru. Here the complex Chavín religious iconography may well have been communicated to very distant areas by means of painted cloths.11

Banderas iconography as known consists mainly of bellicose motifs related to war and sacrifice. Motifs tend to be arranged in a band around the circumference of the exterior of cups and chalices; this can be divided into bands or delimited fields, but more commonly is not (fig. 6). Design areas are often set off top and bottom or on the sides by simple single or double stripes in white, white and red or white and black. Some patterns, such as flags or shields are less rigidly spaced. On flat bottomed, flaring bowls the decoration on the sides is often simple geometric motifs, where Mexican Mixteca-Puebla Polychrome of the same and later time periods would have elaborate step frets or other complex geometric designs. The tondo itself is a large, single motif, most commonly a feathered serpent head (fig. 7). It should be noted that this particular motif also appears as a tondo on huacales of the most common local polychrome style, Acelhuate Geometic Polychrome, which is found in association with Banderas Polychrome.12 The feathered serpent motif is one which was popular in southeastern Mesoamerica, although is better known from the Late Postclassic where it appears on Nicaraguan and Costa Rican Vallejo Polychrome and Luna Ware, sometimes in conjunction with the Cipactli or Earth Monster motif, also of Mexican origin.13

Other common motifs include skulls, rib cages, and crossed bones, often bloodied. The skulls usually have hair arranged to form a column, comparable to the temillotl coiffure of Aztec warriors, suggesting that this element in the Aztec class and sumptuary system is of far earlier origin and was adopted by the Aztec on their arrival in the Valley of Mexico.14 The far more ancient and highly developed cultures of southern Mexico (in the arts) need to be carefully examined for their specific contributions to what, some 400 plus years after the depiction of the temillotl in Salvadoran Banderas Polychrome ceramics, became an important insignia of rank in the Valley of Mexico (fig. 6c).

It is not just the temillotl that appears in Banderas Polychrome ceramics but the earliest known versions of the tlapiloni, a headdress which among the Aztec was awarded to high ranking warriors for exceptional valor in battle (figs. 8a and b). The tlapiloni on Banderas Polychrome is remarkably similar to those depicted in Aztec pictorials, with two elaborate feather tassels connected by a long cord; for example it is clearly related to the Aztec ones years later as can be seen from the drawing of a tlapiloni in the Matrícula de Tributos and the image of an Aztec warrior with a tlapiloni from the Primeros Memoriales (262r). It also has a spotted band, perhaps the skin of one of the spotted wild cats margays, ocelots, even jaguars of the region or, perhaps, of blood or rubber spotted cloth, materials equally used in Late Postclassic ritual display systems. We do not know the significance of this headdress in Early Postclassic El Salvador but its occurrence with other motifs related to warfare is suggestive that it was already a headdress associated with military valor and sacrifice.15

Blood spotted crossed bones and flying rib cages are likewise common motifs that suggest warfare and sacrifice (figs. 6b and c). Dismembered body parts also refer to customs of dismemberment of sacrificial victims better known from Late Postclassic Central Mexico (fig. 9).

A vase discovered in the royal palace area of Cihuatán's Acropolis shows a procession of eagles carrying maguey spines, probably a reference to war and to bellicose display, as well as to self sacrifice (fig. 10). Maguey spines are relatively common as dispersed elements on Banderas Polychrome ceramics, as are also symbolically charged objects including puffs of eagle down, spotted guilloches, star/eye symbols, often in a band as if indicating that the designs pertained to action undertaken in the night, undulating ribbons or banners, and tricolor flags. Some huacales, in place of polychrome designs on the interior bottom, have black lines and hooks painted on the red background, much as what is seen in Mixteca-Puebla pieces. These could refer to blood, as has been suggested for later manifestations of Mixteca-Puebla Polychrome.16

Another motif, and one which places Banderas Polychrome firmly in the Early Postclassic Period is a pendant or necklace identical to those represented on Tohil Plumbate ceramics (fig. 11). Tohil Plumbate is, of course, the hallmark of the Early Postclassic, appearing at the beginning of that epoch and disappearing sometime shortly before ad 1200. Tohil Plumbate is common in all contexts at Cihuatán, and Banderas Polychrome has been found in situ with Tohil Plumbate at that site.

A rare design appears to be flowers, although these sherds, from two vessels found in the Great Hall of the Acropolis, are very badly eroded. Flowers too were later associated with sacrifice and death.

Animal representations are uncommon, save for the highly stylized Quetzalcóatl, although a huacal in the Peabody Museum of Harvard University, in a variant Banderas Polychrome substyle, seems to depict a coyote.17 To date representations of humans are rare, although one depicting a very long-nosed individual has been excavated and compared with the "Nose Gods" Ek Chuah and Yacatecuhtli, god of merchants and spies. Thus reinforcing our ideas concerning the importance of far-flung trading ties between Cihuatán and Mexico (fig. 12).18

However, the most outstanding characteristic of the iconography of Banderas Polychrome as known from Cihuatán is that more than 90 percent of all pieces found to date are decorated with the chimalli or shield bundle, in later times the symbol for war itself in chimalli, in mitl "the shields; the spears," a common metaphor for war in the Aztec languages. This motif is strikingly similar to later chimallis in central Mexican art, such as those painted on the wall of the structure excavated at Tehuacan Viejo, Puebla.19 The Banderas shield bundles all show essentially the same sort of shield. This is circular and apparently made of wood or reed slats with a double or triple, colored, circumferential band (figs. 13 a, b, c). The shield has a number of spears behind it and, often, a spear thrower and/or flags. It is decorated with puffs of eagle down, feathers, and ribbons. Chimalli depictions differ in these latter details; some having literally piles of down puffs; others only a few or some without a spear thrower. The pointed heads of the spears too can also differ in color: some are black and white; some are red and yellow.

Given the context of these vessels—most have been found within the confines of the royal palace and associated ritual or governmental structures—it is tempting to see the bellicose themes of these highly decorated and unusual ceramics as being a visible manifestation of the power of the rulers and the subordination of the lower classes. This iconography might also refer to the means of establishing and maintaining the Cihuatán realm and to its relations with its neighbors—there are many Cihuatán Phase sites on the valley floor and the slopes of the Volcán de Guazapa that may have been subordinate to Cihuatán. Combined with the rarer images of battle, death and sacrifice it is evident that Banderas Polychrome ceramics bore a message. In other words, these were not simply colorful decorated vessels, as most Copador vessels —with highly programmatic designs of stylized human or animal figures and abstract "glyphoids"—we are presented with a definite message of implied prowess in violence and sacrifice.

The Early Postclassic is known to have been a time of political instability and widespread warfare. Within a century to a century and a half after the foundation of Cihuatán, the city was destroyed by fire. This conflagration was enormous and very rapid.

Excavations both in the monumental center and in the surrounding residential neighborhoods have revealed that people simply fled, or perished, leaving their belongings where they were using them to be crushed on the floors by the falling walls and roofs of the buildings. Spear points are commonly found in the burned layers and the only human remains we have encountered in the Acropolis excavations were male crania (and a humerus), caught in drains and obviously pertaining to the violent end of the city.

It was not only Cihuatán that perished: the available evidence shows that all the known Cihuatán Phase sites in the country were similarly burned and abandoned, although the abandonment was not as complete and permanent as it was in the Acelhuate Valley.

With the rapid disappearance of the Cihuatán Phase, Banderas Polychrome pottery also disappeared. Unfortunately, there has been little scientific archaeology in El Salvador, especially with regards to Postclassic sites, so that what happened next is unknown. The ceramics of the historic Pipil, a group which probably did not arrive until sometime in the Late Postclassic, are very different and have nothing whatsoever in common with the ceramics of the Cihuatán Phase.20 Unfortunately the Early Postclassic has not been prioritized for investigation in the rest of Mesoamerica, leading to a dearth of comparative material, whether we are dealing with ceramics, architecture, settlement patterns or any other cultural manifestation of the time.

A great mystery is, in fact, simply the origins of this substyle of Mixteca-Puebla Polychrome. We can posit that the artisans and technology did not appreciably change from the Classic Polychrome workshops; but the style is completely new in El Salvador. Moreover, as far as we can tell, it is limited to this brief episode in prehistory: the brief flowering and rapid disappearance of the Cihuatán Phase. There is one example, unfortunately looted, which suggests the hypothesis that Mixteca-Puebla Polychrome derives in technology and some aspects of style and iconography from Classic Maya ceramics as Alvarez Icaza has suggested.21 This plate has very attenuated glyphoids and the eroded tondo apparently depicts one of the long jawed, semi-skeletal Maya deities (fig. 14). Otherwise we have few clues save the obvious: this iconography is stylistically and thematically allied to that seen in southern Mexico in the Postclassic. It is possible that the Mixtequilla area of Mexico might be involved; one substyle of Banderas Polychrome is red, white, and black, rather than a true polychrome, and resembles somewhat pieces of the Late Postclas-sic Mixtequilla although it is decorated with the same motifs and forms as the codex pieces (fig. 11). There is also some sharing of motifs with local geometric polychromes and, of course, Banderas Polychrome is found in the same contexts as a plethora of other decorated wares including a series of local polychromes, Nicoya Polychrome, a local version of Fondo Sellado, and the plumbates.

To date there are few clues as to the processes which led to the appearance of Banderas Polychrome, including the specifics of the cultural dynamics behind the appearance of the Cihuatán Phase. On the basis of current evidence we can suggest only that the so-called Mexicanization of the Postclassic Maya realm was as complex and as varied as was the mosaic of cultures and cultural influences that we see in other parts of the Mesoamerican Postclassic.

1. Paul Kirchhoff, "Mesoamérica, sus límites geográficos, composición étnica y caracteres culturales," Acta Americana, vol. 1 (1943): 92-107. Actually, Kirchhoff did include western Central America down to the Gulf of Nicoya, but this was rapidly forgotten and the Lempa River appears as the boundary on published maps shortly after his pioneering attempt to separate out this major cultural area from those of North and South America.

2. Luis Casasola García, "Notas sobre las relaciones prehispánicas entre El Salvador y la costa de Veracruz, México", Estudios de Cultura Maya, vol. 10 (1976/1977): 115-138; Karen Olsen Bruhns and Paúl E. Amaroli B., La arqueología de Cihuatán, El Salvador: una ciudad maya del Posclásico temprano (Saarbrücken: Editorial Académica Española, 2012).

3. Karen Olsen Bruhns and Paúl E. Amaroli B., "A Reappraisal of the Cihuatán Phase: Early Postclassic Culture in Western El Salvador", Journal of Central American Art and Archeology 1, University of Calgary, in press.

4. Karen Olsen Bruhns and Paúl E. Amaroli B., "Eighty-five Years of Investigation at Cihuatán, el Salvador", paper presented at the symposium Looking Back, Looking Forward: Seventy-five Years of Archaeology in Pacific Central America. 75th Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, April 14-18, 2010, St. Louis, MO, Arqueología Iberoamericana 20, in press.

5. Although some scholars have suggested that Cihuatán was established by the earliest Pipil migrants, this currently seems very unlikely because the city (and affiliated settlements) was burnt to the ground and never reoccupied. As far as is currently known, the material culture of the Pipil, who were conquered by the Spanish some 400 years later, completely lacks any recognizable continuity with the Cihuatán Phase.

6. Karen Olsen Bruhns and Paúl E. Amaroli B., "An Early Postclassic Round Structure from Cihuatán, El Salvador," Arqueología Iberoamericana, núm. 2 (April-June, 2009): 235-245.

7. Cf. Eduardo Noguera, La cerámica arqueológica de Cholula (Mexico: Editorial Guaranda, 1954); Geoffrey McCafferty, The Ceramics of Postclassic Cholula, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Monograph 43 (Los Angeles, University of California, 2001).

8. Karen Olsen Bruhns, Cihuatán: an Early Postclassic Town of El Salvador. The 1977-1978 Excavations, Monographs in Anthropology 5 (Columbia: University of Missouri, 1980), 2031, figs. 6a and 6b.

9. Jane H. Kelley, Cihuatán, El Salvador: A Study in Intrasite Variability, Publications in Anthropology 35 (Nashville: Vanderbilt University, 1980).

10. To date we have tentatively identified the "Codex" substyle and the "Sencillo" substyle, the latter consisting only of the large service bowls from the Acropolis. Excavations in Platform Q-40 in 2012 uncovered a nearly complete plate of an entirely different substyle also known from two sherds from the Acropolis Palace, which we have tentatively named Calaveras after its most prominent motif. Other substyles are evident, but are known only from pieces in private collections.

11. Karen Olsen Bruhns, Ancient South America, World Archaeology Series (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 131.

12. Bruhns, Cihuatán: an Early Postclassic Town, n. 7, fig. 33b, an Acelhuate Geometric Polychrome tripod huacal from the so-called Southeastern Patios room group located in the Western Ceremonial Center just to the south of the main pyramid.

13. Cf. Claude Baudez, Central América (Geneva: Editorial Nagel, 1970), figs. 93, 96 and 97.

14. An alternative explanation would, of course, be that of George C. Vaillant who, in 1938, suggested that many of the more "civilized" aspects of Aztec culture were, in fact, of Mixteca-Puebla origin. George C. Vaillant, "A Correlation of Archaeological and Historical Sequences in the Valley of Mexico," American Anthropologist 40, 4 (1938): 535-573.

15. Paúl E. Amaroli B., "An Early Postclassic Tlapiloni," unpublished document, 2011.

16. Erendira Camarena Ortiz, "Los tres estilos de la cerámica mixteca del Posclásico," paper presented at the symposium The Origins, Development and Distribution of the Mixteca-Puebla Ceramic Style. 54th International Congress of Americanists, Vienna, July 15-20, 2012.

17. Peabody Museum #58-34-20/70902.1. A tripod bowl from Valle El Salitre, Municipio of Nejapa.

18. Karen Olsen Bruhns and Paúl E. Amaroli B., "Yacatecuhtli in El Salvador," Mexicon 31, no. 4 (August, 2009): 89-90.

19. Edward B. Sisson and T. Gerald Lilly, "A Codex-Style Mural from Tehuacan Viejo, Puebla," Ancient Mesoamerica 5, no. 1 (1994): 33-44.

20. Paúl E. Amaroli B., "Algunos grupos cerámicos pipiles de El Salvador," manuscript at the Secretaría de Cultura and fundar. www.fundar.org.sv, 1992.

21. Isabel Alvarez Icaza, "La cerámica policroma de Cholula. Sus antecedentes mayas y el estilo Mixteca-Puebla," paper presented at the symposium, The Origins, Development and Distribution of the Mixteca-Puebla Ceramic Style.

Información de los autores

Paúl E. Amaroli B. Licenciado en Arqueología por la Universidad de Vanderbilt, codirector del Proyecto Arqueológico Cihuatán (FUNDAR) desde 1999, coautor junto con Karen Olsen Bruhns de La Arqueología de Cihuatán; El Salvador: una ciudad maya del Posclásico temprano, y The Archaeology of Cihuatán El Salvador: An Early Postclassic Maya City. Autor de múltiples informes sobre la arqueología de Cihuatán y otros sitios salvadoreños. pamaroli@yahoo.com.

Karen Olsen Bruhns. Doctora en Antropología por la Universidad de California, Berkeley, Profesora emérita en Antropología por la Universidad Estatal de San Francisco (California), directora del Proyecto Arqueológico Cihuatán (FUNDAR), desde 1999. Autora de Ancient South America; Women in Ancient America; Faking Ancient Mesoamerica y Faking the Ancient Andes, entre otros. Autora de monografías sobre Cihuatán (El Salvador), los Quimbaya (Colombia), y Chontales (Nicaragua) y diversos artículos especializados sobre sus investigaciones en Colombia, Ecuador y El Salvador. kbruhns@sfsu.edu.