Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica's (1937-1980) works known as Parangolés are frequently

discussed as the culmination point of his longing for the liberation of color into

space and the empowerment of the interacting user; and some questions remain open,

for example, in what exactly do the invention and creativity of which Oiticica speaks

in this context lie. Is it sufficient to actively engage with the Parangolé capes?

The artist would probably say that, no matter which action is accomplished, it is

better than dropping back into the contemplative attitude of the traditional way of

viewing art. Nevertheless the idea of the supra-sensorial as heightened perception

far exceeds the mere sensorial. Thus this contribution proposes a way to imagine the

issue by adopting an image-theoretical perspective.1 Through a close reading, or rather a close viewing, of existing photo and film documentations

of Oiticica's works as primary sources, this approach seeks to interrogate related

passages in his writings (instead of taking the latter for granted) in the hope that

it will complement, clarify or flesh out the written statements.

Film Footage in

H.O.

and

Heliorama

Ivan E. S. Cardoso, a filmmaker from Rio de Janeiro, interviewed and filmed his friend,

the artist Hélio Oiticica in January 1979. The film portrait H.O.2 originated from this encounter. It is a collage of archive photographs, existing

film footage from the 1960s and newly recorded scenes. According to the curator Cristina

Cámara Bello, the film summarizes the essence of the œuvre by the Brazilian artist.3 This is quite a claim for a film of almost thirteen minutes that, moreover, seems

to hardly demonstrate any systematic structure at all. In contrast, the filmic documentary

H.O. Supra-Sensorial: A Obra de Hélio Oiticica (1999) by Katia Maciel, is well suited as an introduction because it provides an

overview of Oiticica's work phases in a well-balanced manner, in chronological order

and competently with (few) words and (many) pictures.4 Moreover, it stands out due to two attempts to do justice to the artist's visions

when presenting his works. On the one hand, H.O Supra-Sensorial is also available as an interactive CD-ROM with a navigable menu, providing a labyrinthine

exploration between colors, texts and projects, etc.5 On the other hand, in the linear film version, a pace was chosen that guarantees

the viewers time enough to adjust to the impressions. The camera moves fluently and

without rushing through the exhibition spaces and around the works; it approaches

the reliefs and draperies, provides close-ups and shows how the Bólides can be used.

Felipe Sá (camera director) catches sensations such as those a fearless audience (as

imagined by Oiticica) would have experienced when viewing his pieces. Even though

Maciel's documentation aims to present Oiticica's œuvre-within the scope of the chosen

medium-in the best possible way, and even though by doing so it stands in considerable

contrast to H.O., I nonetheless agree with Cámara Bello that Cardoso's film (actually two of his

films) capture the main core of Oiticica's pursuit.

As for Cardoso's other film Heliorama,6 it is predominantly conformed by the same historical records, but this time they

are not accompanied by the artist's declarations; instead, it is furnished with fragments

by the poet Haroldo de Campos and others. While Maciel's film takes on a deliberate

explorative stance as to the role the audience might play, in Cardoso's films it is

primarily about the artist himself, who is involved with those "non-contemplative

activities," which he-as "instigator of creation,"7 initiator of states of invention,8 "'entrepreneur,' or even 'educator'"9-proposes to the recipients of his art as an experimental setting by providing the

necessary paraphernalia. Oiticica accompanied his visual-artistic œuvre with extensive

thought filled writings which scholars constantly and excessively quote. It is hardly

enough just to pair his elaborate written thoughts with a certain group of work. My

pursuit is to overcome this shortcoming and to analyze Oiticica's active engagement

with his pieces, as preserved by films documenting them.

Is it thus possible to define his ideas more precisely or to accumulate further well-grounded

material-based evidence to understand them? For this purpose I will refer to three

motifs at large: each time, the artist operates outdoors with a Parangolé. One of

these motifs appears only in Heliorama and is edited. The other two are present in both films. Each time they were cut in

a different manner and the segments are distributed throughout the films. In the interest

of simplification, I name these sequences by the title of the work.

Sequence

Parangolé P4 Cape 1

The Parangolé P4 Cape 1 (1964) is a very complex assemblage of different cloths, some up to 150 cm long,

colored red, bright blue, white, lemon yellow, and different shades and tones of orange;

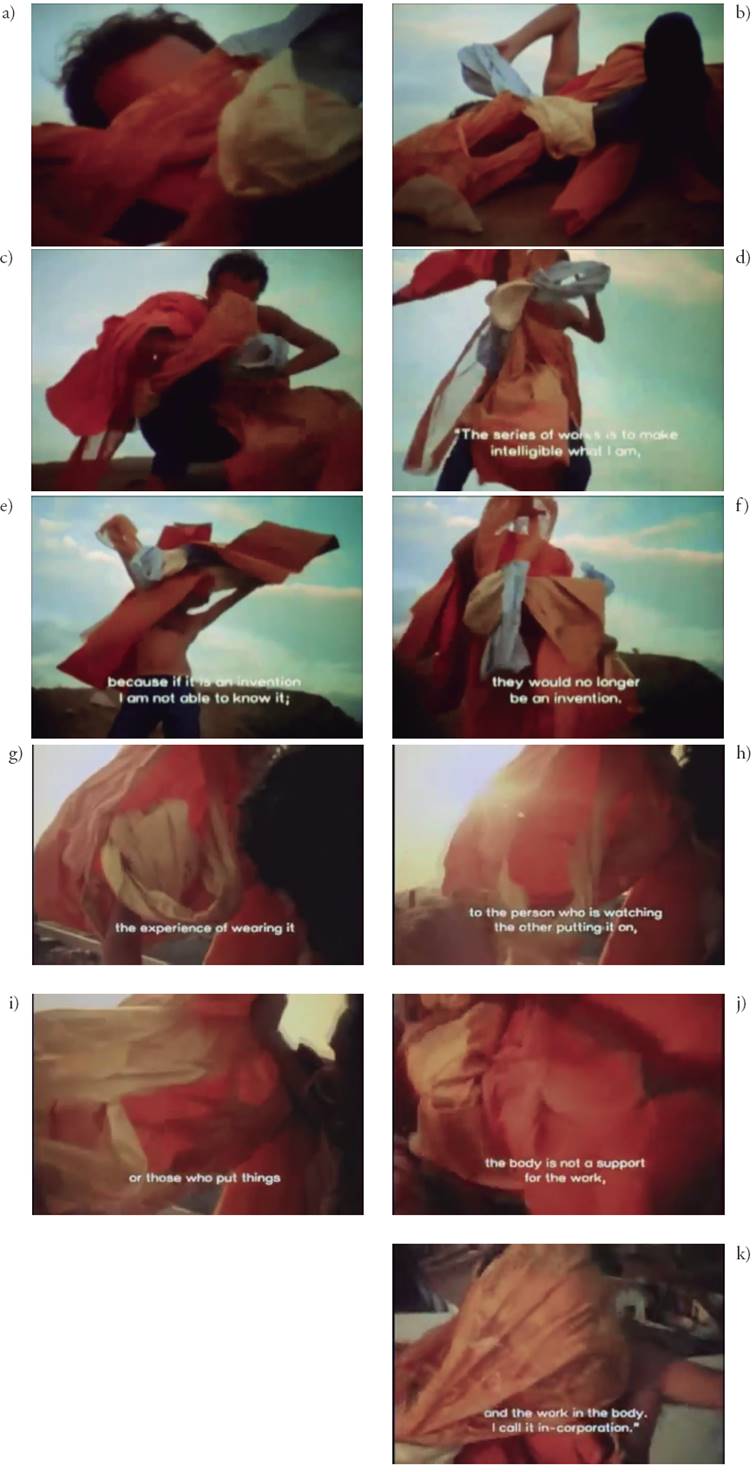

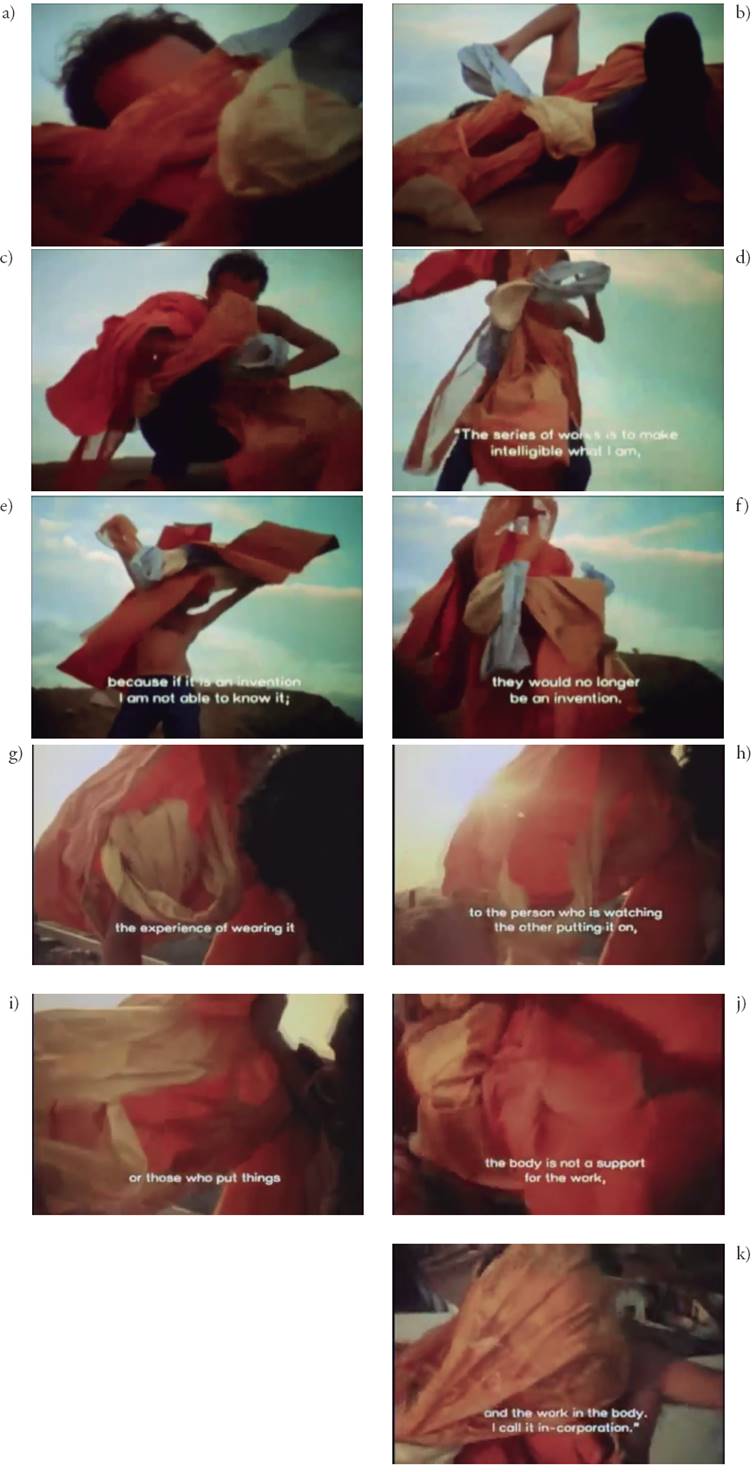

wrinkled and patterned, smooth, almost transparent. In Heliorama, the sections with the Parangolé P4 Cape 1 appear three times: 0:21-0:38 (figs. 1a-1c). At the beginning, only Oiticica's forehead and a tuft of hair are shown; his face

is concealed by a cloth strap. He is about to let his slightly straightened upper

body sag again. Then the camera zooms out a bit and reveals that the artist is mostly

lying on his back on a mound of soil, intimately entwined by the Parangolé, with one

leg angled. With his arms he keeps the fabric loops in motion, he acts in an improvised,

playful manner as if with a lover. He burrows himself into this colorful cloth ensemble

elaborately sewn together. Then, without using his arms, the artist unpretentiously

gets up while he continuously distributes the Parangolé over his naked upper body.

He bends slightly forward and keeps his gaze directed towards the entanglement in

his arms in front of him. Eventually, he raises one arm together with the cloths,

at a slant.

3:52-4:09 (figs. 1d-1f). This time the artist can be seen descending the hill in a full shot as he approaches

the camera. At all times his face remains covered-far too long and too consistently

for it to be fortuitous-by some of the many parts of the fabric, thus leading one

to wonder how he can avoid falling down the embankment, given that he has no clear

view. He swings his upper body in all directions, while stretching his arms out somewhere

and maneuvering parts of the Parangolé. Quicker movements alternate with slow flowing

ones, however these are definitively not dance steps. At no point in time did I have

the impression that it is about a graceful performance outwardly oriented intended

to be seen by the spectator as elegant.

7:15-7:19: In this short scene the artist is still standing at the same spot, his

upper body tangled in a muddle of cloth. Externally, little happens; he is hardly

moving. The fabric's movements seem rather to be caused by the wind. Two issues will

be noted here and elaborated later. First, for Oiticica, the body and especially the

eyes are involved in a creative act: "the real 'making' would be the individual's

life-experience".10 Only with this in mind can the statement "Looking can be like dancing"11 be understood, and one can rightly ask: where, then, does the productive moment actually

lay? I will come back to this point later. Second, what de Campos writes in his text

"The Open Work of Art" (1955) and which Oiticica mentions several times, must be considered.

Therein, de Campos quotes the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre and the composer Pierre

Boulez who express the concern that in poetry and music the break, the pause, should

not be disregarded as it is an element of rhythmic organization.12 As soon as pauses become important, it is an indication of a time-based arrangement

being involved. Those who wear the Parangolés decide how fast they move. There is

no need to rush and they can also envision various velocities.

In H.O. three further moments of this motif exist. Firstly, in 1:07-1:58 the above mentioned

scenes can be seen en bloc. In this case Oiticica, when coming down from the hill,

approaches the camera to the point where an orange cloth fills the entire monitor

and darkens it because he has practically covered the lens. 4:19-4:25 (figs. 1g-1i): Now the camera stands to the left of the artist whose head is visible at the right

edge of the image. This time, Oiticica's percept seems more or less to correspond

with what is presented to the viewer in the middle of the image. With his right arm,

he holds up crumpled yellow and orange cloth panels and twists a yellow scarf-like

appendage with his left wrist, producing ever more new drapes. As Oiticica holds everything

towards the sun, additional interplays of light and shadow evolve, the colors light

up. The artist does not pay attention to what he does with his hands, but to its effects.

4:33-4:36 (fig. 1j): What can be seen is only cloth panels in motion, however the color combination

reveals that this is still the same Parangolé. Due to missing cues it is difficult

to judge whether the camera is gliding alongside the orange, bright orange, yellow,

pale-bluish fabrics or whether Oiticica-wrapped within them-rolls along.13

4:40-4:48: The orange-wrinkled cloth panel is mummy-like, tightly wound around the

artist's head. It is mostly due to the way the camera approaches the cloth, rather

than to its form, that the viewers notice there is a face behind it. Towards the end

of this scene this turns out to be the case (fig. 1k). What curator and art critic Guy Brett finds as regards the Penetrables also serves

as a thought-provoking impulse for the phenomena at hand when he writes of: "veiling

sight as perhaps the most elementary and primordial pleasure in our visual relationship

to world."14 When Oiticica wraps and coils cloth around his head, for him it is not a covering,

occluding, or shielding. If I am correct, behind it he constantly keeps his eyes open

in order to let various levels of sensory input merge together. This is also to be

assumed in the second film passage.

1a-1k).

Sequence

Parangolé P17 Cape 13

This action with the simpler P17 Cape 13 "I am Possessed" (1967) was fixed on black-and-white film by Ivan Cardoso in 1979 and was used only

in Heliorama: 10:32-10:55 (figs. 2a-2c): The image section shows Oiticica's upper body obliquely from above; he is rolling

on the ground. A dark cloth loops across his back, diagonally crosses his chest and

is wound over his left upper arm. A pale, longish, semi-transparent gauze (the red

inscription "estou possuído" is not legible here) is attached to it. Oiticica holds

the gauze from its free end where something cushion-like and beige-colored is sewn

into a plastic bag. He makes sure the over dimensioned gauze bandage always blankets

his face.

2a-2c).

The left arm merely serves to support his rolling body over the uneven earthy terrain,

a motion which takes place without haste so as not to hurt himself. The cushion-like

appendix filled with straw15 at the end of the gauze is not used in order to soften the fall; instead, it is constantly

kept in the air. So, like the veil in front of the artist's eyes, it is certainly

not a protective measure. Rather it structures or alienates his perception of the

near outside world: sky, meadow, soil that because of his rolling periodically appears

as alternating flashes of azure, green and sepia, as seen through the unifying bright

textile.

The art historian Tatiane de Oliveira Elias pointed to the connection between the

Parangolé P17 Cape 13 and the Orixá cult of the Afro-Brazilian Umbanda religion.16 The dances during the rites of the Orixá cult resemble the Samba; it is all about

trance, in so far as the "possession trance" plays an important role. Then, the persons

in trance receive a white bandeau, called oja, wound around the upper part of their bodies and they wear oxu, a conical pack of ingredients that protect the sacred cuts received during the initiation

rite. The priest or priestess is considered to function in a creative capacity causing

the novices' birth. In this sense, art historian Mikelle Smith Omari describes the

procedure as follows:

The basic ritual consists of the sacrifice of a white dove or pigeon, whose neck must

be wrung in a special ritual manner rather than cut. The blood is placed on the head

of the individual along with other sacred items such as kola nut and some of the favorite

foods of the orixá owner of the individual's head. [...] Tiny portions of all the food and the sacrifice

are placed on the tongue, palms of the hand, soles of the feet, and the forehead of

the novice before finally being placed in tiny bits in the center of his or her head

and in the food receptacles of the orixá. Finally, a long white cloth is wrapped around the head of the individual and tied

tightly. This head-tie serves to secure the items placed on top of the head during

the night-long seclusion of the individual after the ceremony.17

It is reasonable to suggest that Oiticica was familiar with the initiation rites of

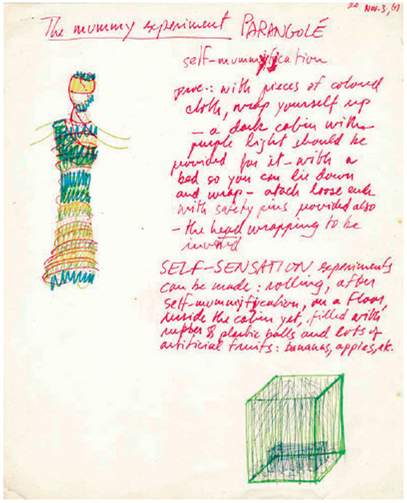

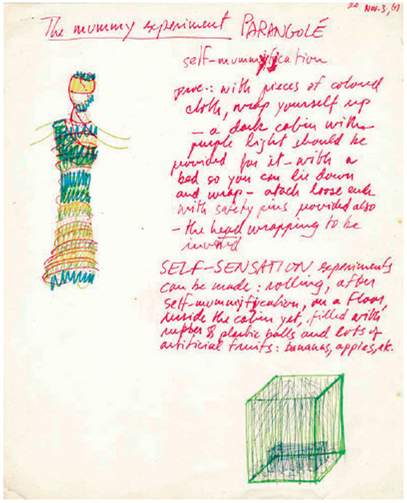

the Candomblé, as loans also seem to reappear, for example in Head Parangolé (1979), in an altered manner. In 1969, Oiticica conceived the Parangolé Self-mummyfication, which is embedded within a related line of action: in a dark cabin with purple light

a person, on a bed, wraps herself/himself from tip to toe (including the head) in

colored cloths (fig. 3). Afterwards, the person rolls around the bed, "on a floor, inside the cabin yet,

filled with rubber & plastic balls and lots of artificial fruits: bananas, apples,

etc."18 While Brett assumes that the Parangolé Self-mummyfication stems from a striking contradiction-a dispositif of liberation on the one hand and

simultaneously a sensory deprivation,19 on the other-it is also possible to find at least an analogy to existing Orixá ritual

practice. I understand this piece in different terms, primarily in those that parallel

Oiticica's use of the Parangolé P17 Cape 13. The artist himself called it an experience of "auto-sensation."20 Regardless of the extent to which the person is wrapped from head to toe in the Parangolé Self-mummyfication, the rolling automatically affects the hands, which as principal organs of touch

used to identify objects quickly, are dethroned from their outstanding position regarding

this task and from their habit of measuring. The entire body's surface serves as a

large scale tactile sense organ that collects impressions in many places at the same

time and that only to a lesser degree works in terms of object determination.

3.

Work Concept of the Parangolé

Oiticica developed the Parangolés between 1964 and 1978. They consist of burlap bags,

torn cloth, nylon, fabrics, semitransparent plastics, belts, strings, and ropes. Numerous

attempts have been made to grasp what it is essentially about. It has been described

as: dress-objects seen as wearable or even inhabitable paintings ("d'objets-vêtements

[...] comme des peintures à porter, voire à habiter"),21 textile works to sheathe and operate ("zum Überziehen und Agieren"),22 sculptural costumes ("skulpturale Kostüme"),23 "canvases for wearing, for going out into the world and for communicating in the

free spontaneous exchange of the samba experience,"24 "painting[s] in which 'support' and 'act' are fused,"25 "hang-glider[s] of extasy,"26 and as "transcendental robes [...] quasi-impossible to wear," but with the potential

for multiple meanings when they are tried on.27 They "were a cross between a banner and a cape and were designed to be lived and

danced in."28 Evaluations from a material analysis and conservation point of view are also helpful.

Restorer Wynne H. Phelan understands the Parangolés as "ultimate color structures.

They are flexible and un-predictable forms. The entropic motion of the person wearing

the Parangolé prescribes the way light interacts with color, texture, and sheen. The

Parangolés are not costumes; rather, they are layered fabric structures."29 While secondary literature locates the Parangolés, given their material condition

and formal quality, mostly as oscillating between paintings and garments, Oiticica

emphasizes, in contrast, that he is not interested in relations of similarity to existing

things.30 It is striking that he describes the Parangolé functionally, as an "open-ended object."31 "The cape is not an object but a searching process, searching for the roots of the

objective birth of the work, the direct perceptive moulding of it. [...] It is more

a constructive nucleus, laid open to the spectator's participation, which is the vital

thing."32 He also names his works programs, "situations to be lived,"33 "auto-performance proposition[s],"34 or "sensuality testers."35 This indicates that the Parangolé is to be seen as a configuration for another actual,

an ephemeral concern. Such a cape is nothing without its use.

Weighted Double Use of Parangolés

To this day I have found two reports based on self-experiments with Parangolés. The

first comes from the art historian Anna Dezeuze. In order to get a fresh look at this

group of works, she chose a practical approach. In December 2002 and March 2003, together

with the photographer Alessandra Santarelli, she conducted indoor and outdoor experiments

in London. The personal experience of wearing a Parangolé as well as the photo series

from two sessions were designed to aid her to "explore the nature of the relation

between the artist's formal experimentation and his political objectives."36 Wearing the cape with the banner "Sex and violence, this is what I like" in public,

led to an increased awareness of her own appearance and look. Simultaneously, being

a white middle-class European female, a feeling of inauthenticity rose in her when

faced with this message, that is, the impression of taking on another persona, and

finally interpreting a long piece of gauze as a caudal body extension.37 On the other hand, for Dezeuze, the studio photographs seemed to more strongly foreground

the formal qualities as an effect of a precise determination of illumination and contrast.

However, when Dezeuze writes in her conclusion, "Parangolés encourage a 'supersensory'

state of absorption,"38 it must be assumed that she could not derive these insights from her practical experiences

because according to her own report she was not "with it." The findings would have premised the embodiment of what the artist meant

when he said it is about

overcoming the structuralism created by the propositions of abstract art, making it

grow on all sides, like a plant, until it embraces an idea focused on the liberty

of the individual, furnishing him with propositions which are open to his imaginative,

interior exercise-this would be one of the ways, provided in this case by the artist,

of de-alienating the individual.39

Dezeuze's analysis focused mostly on the external impression: a factor which Oiticica

in turn saw as but a welcome secondary effect. Those looking at the "performer" can

slowly feel themselves partake, they warm up, get into the mood or atmosphere to a

certain degree, until it is their turn to perform, i.e. to really live it from within.

It is striking how many authors have picked out passages from Oiticica's "Notes on the Parangolé"

40 (1964-1965) without following his postulated hierarchy between the two kinds of participation.41 People speak of an (egalitarian) mix of experiences while wearing, watching, and

looking back at viewers or of the 'dialogical nature' of the Parangolé in introversion

and extroversion: "This invention allowed the extroversion-the performance, the mediation

of a message for the spectators-and at the same time the introversion-the personal

and introspective exploration of the material coils."42

Nevertheless, upon reading the artist's writings, another emphasis can be detected,

in so much as Oiticica speaks of "primary" and "secondary" meaning.

My entire evolution, leading up to the formulation of the Parangolé, aims at this magical incorporation of the elements of the work as such, in the whole

life-experience of the spectator, whom I now call "participator." [...] "Wearing"

in its larger and total sense, counterpoints "watching," a secondary feeling, thus

closing the "wearing-watching" cycle. Wearing, by itself already constitutes a total experience since, by unfolding it and having

his own body as the central nucleus, the spectator experiences, as it were, the spatial

transmutation which takes place there: he perceives, in his condition as structural

nucleus of the work, the existential unfolding of this inter-corporal space. There

is, as it were, a violation of his being, as an individual in the world, distinct and yet collective, towards one of participator

as a motor center, nucleus, not only motor, but principally symbolic, inside the "structure-work."43

Oiticica did not denude the upper part of his body in order to expose himself, but

to include the skin as a sensitive organ of perception for experiencing the various

textures and material surfaces. Noticeably and significantly, he always covers his

face, but not in order to withhold it from the public, but in order to pursue his

perception-related experiments. While "doing his own thing," the audience profits

because it can observe a moving mass of color. At the same time, those watching from

outside are never close enough to the event to really be enclosed and to gain the

experience of those who are inside and operate the Parangolé. The distance from what

is happening is consequential and marks a qualitative difference because-according

to my hypothesis-with the spatial distance, the mode of perception directed towards

the object of recognition can hardly be eliminated (and this very point is yet another

hypothesis). For the audience, the Parangolé in movement is always framed by its surrounding.

As for those who operate the Parangolé according to Oiticica's intention, there exists

no viewpoint providing an empowering overview and thus a reassuring position.

The persons immersed channel the focus of their activity towards their own sensory

perception and frame the events through the control of their own movements and the

limited-because mediated-control over the cloths' movements. This moreover is a frame

coming from within. So when artist and art theoretician Luis Camnitzer writes that

Oiticica's "work is not presented for the viewer, but happens with the viewer,"44 I would add "and within the viewer-as-a proactive-perceiver."

In his note "Parangolé Synthesis" ("PARANGOLÉ-SÍNTESE") of 1972, Oiticica offers the

following entry that, in my opinion, mirrors the above mentioned disparity in meaning.

As what is important is not that vestir and assistir are different, but that they are given different importance: vestir and assistir: "non-display ¦ auto-climax ¦ NON-VERBAL ¦ Corporal proposition taken to a level

of open experimentalism."45 What must act in concert are-I will try to clarify this in technical terms-the effectors

as well as the sensors of the human body. In the discussed film motifs, he is not

looking inward introspectively, oriented towards his inner mental/bodily world, oblivious

to the outer world; on the contrary, he is oriented towards the outer world, in order

to actively mold the incoming impressions. This can happen without any perceptible

exterior movement on his part or without the help of others (as with the Parangolés

where the artist himself is the "motor"); however, movement itself is indispensable

in any case.

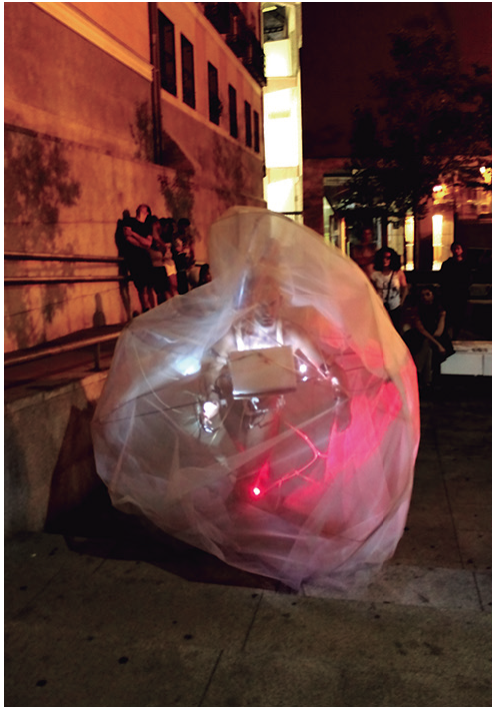

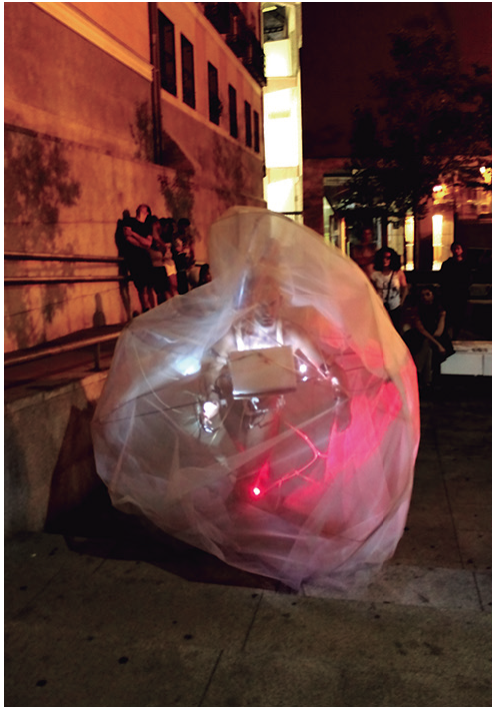

The same holds true for the works by Spanish intermedia artist and post-queer activist

Jaime del Val (b. 1974). As I see it, the metaformance Metakinesphere (2014) which del Val developed within the framework of the interdisciplinary laboratory

Metabody (2013-2018) can be viewed as a technologically augmented successor project

to Oiticica's artistic approach in several respects. With his collaborator Cristian

García-Reverso, del Val conceives it as "a new bond of art and technology, which will

generate new kinds of perceptions and embodied knowledge that put more emphasis on

movement, multiplicity, and unpredictable change."46 The image (fig. 4) shows the performer outdoors and completely enmeshed by a translucent net lace.

This textile configuration is attached to his body at eight points, on the arms and

legs, by flexible curved metal rods, so that each of his movements has an effect on

the entire structure. Additionally, several red, white, and blue light sources attached

to his legs, hands and back guarantee the camera will film close-ups of the performer's

skin. With a portable projector placed on the performer's left foot facing upwards

and projecting onto the surface of the metakinesphere from inside, their live stream

is immediately made visible on the semitransparent tulle and beyond, adding to the

whole flux that the person at the same time controls yet does not have completely

under her/his control. Del Val emphasizes that in this "posthuman cocoon without recognisable

form or function,"47 besides being a "laboratory of perception," the interacting person perceives something

else different than what the spectators receive from the outside, as this kind of

"mobile and tactile vision" demands breaking the distance.48 This evidently coincides with my main assumption regarding the kinds of perceptions

present in the use of the Parangolé and thus attests to the continued interest in

concerns Oiticica set forth more than fifty years ago.

4.

Jaime del Val & Cristian García-Reverso, Metakinesphere, July, 2014. Metaformance, Metabody Forum, Medialab Prado, Madrid.

Immersive Expression for Their Own Multi-sensory Impression

Although in his text "Notes on Dance"49 Oiticica emphasizes how closely the Parangolé principle is to the Dionysian dance,

in the analyzed scenes he is not dancing. Moreover, we do not see him in any other

particularly "representative" occupation. On one occasion he is lying on the floor,

gets up and stamps his feet; in another he rolls down a mound of earth. He does not

appear as a show piece for others. While most of the people from Mangueira, to whom

Oiticica gave a Parangolé, danced and thereby displayed themselves before others in

either a latent or an explicit manner, the artist himself remains unimpressed by the

camera's presence. Even when he dances-he wants to have it understood as an "inventive

liberation of the capacities of play ¦ it's ¦ INVENTION-PLAY"50-it only happens for his self impression, for his own visual and general bodily experience.

If it is about the impression, what does Oiticica mean with the word "expressive act"?51 It is about the immersive expression within each individual's multi-sensory impression:

when the "performer" is engaged in an expressive activity, but this expressive activity

is done primarily for his/her own impression (and not for others that might happen

to be around). The term "immersive expression" implies tension because immersion always

has to do with imposing. This is also the case here, but in combination with a very

active arrangement and reception; its particularly active attitude, and the fact that

the arrangement can also be seen as reception, must be emphasized.

Sequence

B 54 Sac Bólide 4

Another scene now showing Oiticica, in an abandoned shopping arcade, under a transparent

plastic bag (figs. 5a-5c)52 presents movements that come the closest to something that can be termed dancing.

The philosopher Fiona Hughes describes these movements as "a walking that is almost

dancing."53 As for the Parangolés, she takes the following position:

Think of a conversation in which the exchange freely develops without any discernable

constraint. [...] Conversation becomes playful in its structure, open-ended in its

development, and self-sustaining in its motivations. [...] I would also suggest that

when a conversation takes off in this way, we can become aware of the form or pattern-we

might say the stylistic frame-of the conversation quite differently from the normal

case.54

5a-5c).

If one argued that-given the freedom from all constraints-the course would automatically

lead to the creative and inventive, then one would misjudge how much energy has to

be invested in these goals. Oiticica does not distribute the label "invention" carelessly

to an audience that takes his suggestions loosely and interacts however it pleases.

Becoming active and responsible participants (and therein lies the political dynamite)

demands complete self-investment in the immersion and embodiment. In the scenes with

the Parangolés used in Cardoso's films, I was unable to recognize anyone other than

the artist himself, and probably Nildo of Mangueira who reached this goal as well.

In reference to the above-mentioned scene from B 54 Sac Bólide 4 (1966-1967), Hughes regrets the absence of a discernible dance style which would

have been slightly modified by an improvising Oiticica. As she acts on the assumption

that the use of the Parangolés is supposedly an intrinsically harmonious performance

symbolized by the hip swing, she misinterprets this sequence that shows a seemingly

arrhythmic Oiticica, in so much as he calls attention to a crisis:

Is there any jogo de cintura in this second sequence? We may suspect not, for Oiticica's movements are often jerky

and might even appear unbalanced. Nevertheless, I would suggest that his bodily movements

reveal a deeper significance or what is implied by this verbal expression, through

showing the evolution of movement and the risk of its breaking down. He deconstructs

jogo de cintura as an activity of balancing by highlighting its potential crisis. In doing so, he

draws out a deeper possibility within the phrase, highlighting the ongoing project

of improvisation that entails both the difficulty and the achievement of kinetic balancing.55

As I understand the scene, in fact there is no deconstruction and no crisis going

on, but rather Oiticica's improvisation under or inside a plastic bag in which whether

he decides to move jerkily or fluidly, homogeneously or rich in variation, is completely

irrelevant. Only the acting person herself/himself can judge the success of her/his

improvisation. "In that Oiticica's works are interactive objects [...] this interpretation

cannot be separated from the embodied knowledge of the viewer him or herself."56 He does not care whatsoever whether or not this provides an aesthetically valuable

display for outside viewers. What was he searching for in this experiment introduced

as "parangol' helium" in the film H.O.? Through the transparent plastic bag's materiality he most likely perceives the urban

space in a modulated way; the glaring ceiling lights and the display windows optical

reflections refract according to the kinks in the plastic. The artist registers its

crinkling sounds, his steps on the blank pavement stones and the traffic noise. He

notices how the synthetic material, due to his respiration and transpiration, accumulates

more and more condensation, altering his vision and making the bag stick to his back.

He tests what is altered in his perception when he moves towards the darkness. When

he lets the camera enter the plastic hood, he does not attend to it more than necessary.

He seems to be weary and ecstatic; it is probably very (and increasingly) stifling

inside the Parangolé. This action's creative moment consists in consciously living

and absorbing all these components of sensation simultaneously and over a period of

time in an intense manner. The following paragraphs hint as to what is needed for

this to take place.

Parangoplay

Games are often, and plausibly, described as an aggregation of rules (constraints).

Nonetheless, it is possible to elucidate an important aspect from Hughes' parallelization

of playfulness and constraintlessness. Certainly, the unconditioned nature should not be interpreted in such a way as that

the specificity of the experiences that can be had with each different Parangolés

can no longer be distinguished. As Oiticica himself emphasized the experimental and

the play aspects over and over, we may allow ourselves an excursion into this topic.

The psychologist Heinz Heckhausen sees the play of infants as a behavior free of purpose,

which primarily "strives to increase or maintain a certain level of tension and excitement."57 This delightful experience can be created by and for oneself by triggering constellations

of stimuli, which react to and spur on the process of creation. No wonder, writes

Heckhausen, that this normally comes with ecstatic feelings that outgrow and surpass

oneself.58 Interestingly, for Heckhausen all of the stimuli are discrepancies and could-he speculates-serve

as a basis for better grasping psychological aesthetics. His four categories of contradictions

are: novelty/change as a discrepancy between current and previous perceptions; degree of surprise as a discrepancy between current perceptions and expectations fostered by former

experiences; entangledness as a discrepancy between parts of a current field of perception or experience respectively,

for example a mobile; and uncertainty/conflict as a discrepancy between different expectations and/or tendencies involved with the

suspense and risk of one's own acts and that can even extend to a "craving for life-threatening

experiences."59 To my understanding, the category entangledness prevails in the Parangolés. In Oiticica's writings a similar expression is to be

found: "New virtualities are now added to the much more complete thread of structural-color

development that unravels here, and the sense of spectator involvement reaches its

apex and its justification."60 According to Heckhausen, entangledness is distinguished by the fact that it provides an activating effect of longer duration

(longer than the novelty or the surprise).61 One can stimulate oneself by means of the above mentioned categories because not

everything can be anticipated and pre-programmed. This becomes even more evident in

the self-experiment conducted by choreographer Johannes Birringer. It is the second

report based on his own experiences with a Parangolé and it speaks of completely different

aspects than Dezeuze writings do.

When I tried on one of the Parangolés, I actually noticed at first a certain ambivalence as to how to wear them: they seemed

labyrinthine and perplexing, fragmented layers with openings (for head, arms, hands,

legs) creating asymmetry and confusion of inside and outside, and they felt stiff.

I then realized that, contrary to the evocative filmic close-ups, the stiff humble

fabrics did not make me sense erotic pleasure or playful self-absorption in masquerade

but turned my awareness to the outside of myself. I began to animate the colored fabrics

and the stiffer, plastic sleeves toward the others around me observing the color-action

and the refracted light, not knowing whether the body's motion could communicate the

uncertainty of the sensorial source. I did not know the source, my body seemed elsewhere.

Unlike digital interfaces in which gesture or motion controls specific parameterized

reactions and in which one feels monitored, the corporeal processes here are indeterminate:

they manifest whatever color comes to mean as a living action without place. Perhaps

this is what Oiticica's supra-sensorial propositions point to-an inaccessible elsewhere

toward which dance strives through its dispersal of energies. These energies can never

be analyzed precisely and computed. At the same time, as with all strong relational

art, the environment can respond to these energies, sustaining and enhancing the displacement

of bodies from the subjective to the objective realm of experience. The dance of color

is transobjective, fleeting.62

The states of tension and excitement differ depending on whether one is playing or

observing. This raises the question about the possibility of a collective dimension

of such an experience. It seems that in the case of the Parangolés each single person

has to form his/her experience for himself/herself. However, this does not isolate

him/her from the outside world, nor does it lead her to a collective in the sense

of a crowd, because the "stimulus constellations" do not deny their roots, that rest

in the visual arts and in painting more specifically. To this extent they are still

aesthetic-formal in nature, even though-at the time when the Parangolés were developed-this

meant subversively transgressing several borders of established understandings of

art. In order to better outline the specificity of Oiticica's proposals, I contrast

his configurations, which emanate from a core (the Parangolé-wearing human), with

a situation where a collective involvement is predominant and that thus needs the

activation of a larger environment. It is self-evident that what comes to mind is

the Brazilian carnival and, as Carlos Basualdo wrote: "One has to recognize that there

is a bit of carnival in the Parangolé,"63 even though Oiticica's program differs from spectacle and folklore. Here, we compare

his approach with another feast, the Holi-Festival in India. It will serve to speculate

on how a concrete realization of Oiticica's idea of color being literally released

into the surrounding space might look. As his art and the religious traditions in

Northern India are rooted in completely different cultural realms, this comparison

is only meant to carve out formal or structural similarities and differences. Thus,

it is not assumed that the Holi-Festival influenced the artist directly, although

it should not to be discarded without further study.

Hélio-Holi?

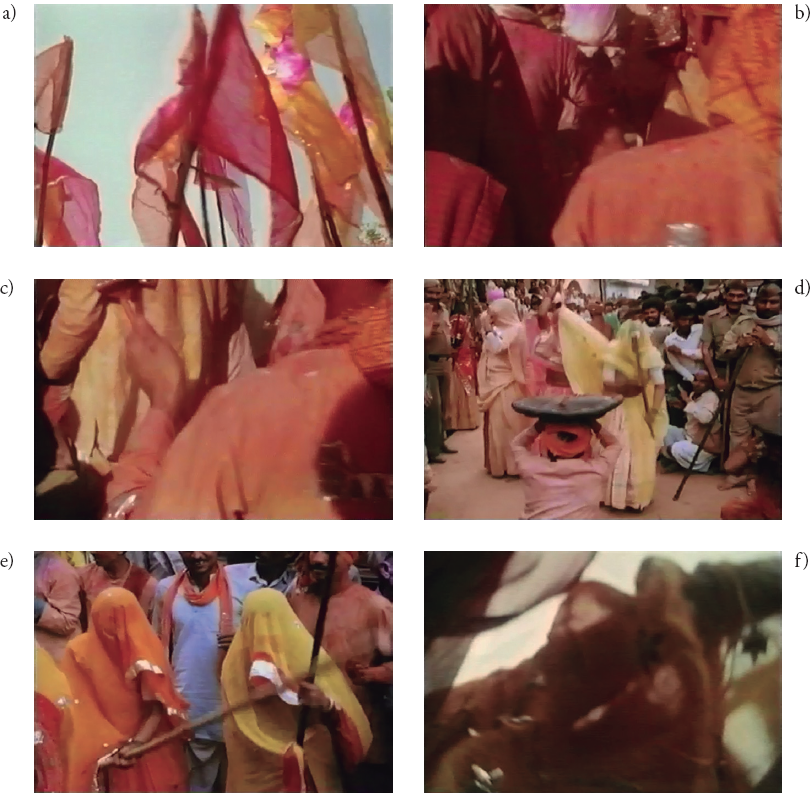

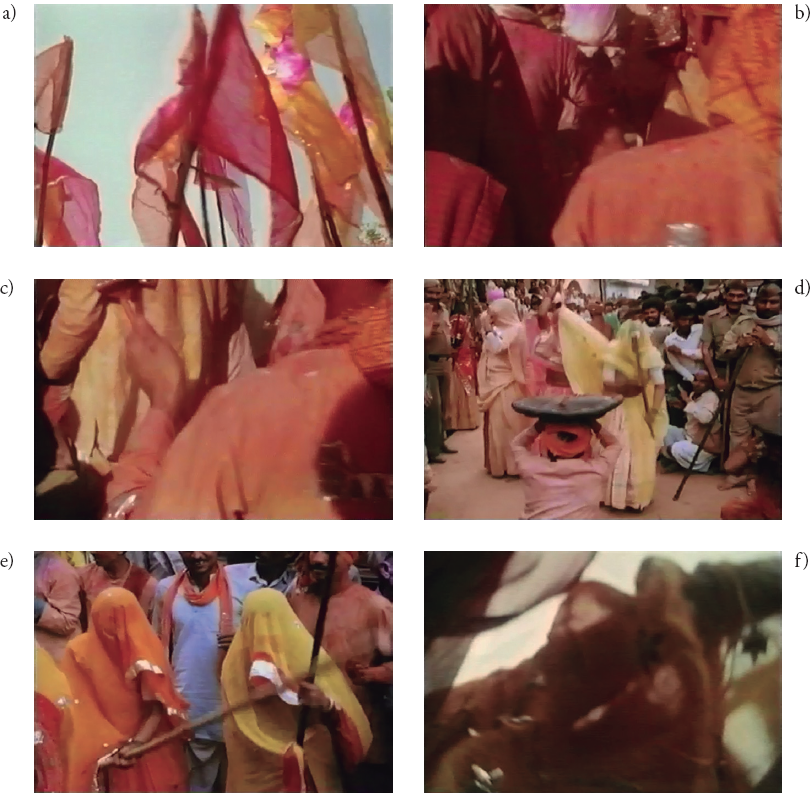

The association of liberated flying colors brings us to India. The Holi festival,

taking place in February-March each year, is the celebration of renewal, rejuvenation,

fertility, love, and the victory of good over evil. Playfulness and spontaneity, dance

(rāsa līlā),64 the play with the colors (gulal, preferred red, saffron, yellow, white, green), the consumption of substances (like

bhāṅg)65 in order to "enter paradise"66 are formal elements that Holi shares with Oiticica's propositions. He, who wanted

to liberate and spread the color into space, would certainly have been fascinated

by this joyful and collective splashing of dye and powder, a revelry carried on for

hours and days which eventually leads to trance-like states. "Holi-in spite of appearing

as the most chaotic and irreligious affair-is in fact deeply charged with spirituality

and religious meaning. It is certainly an intimate and intense spiritual experience."67 This quotation stems from the film Holi. A Festival of Color. A Hindu Celebration (1990, 57'), directed by Robyn Beeche. It traces the pilgrims' route in the region

of Braj and immerses the viewers in the major Hindu religious festival at the full

moon of the month Phālguna, in other words, at the beginning of the year for farmers

in northern India. We see flags and pennants in the village of Dauji (fig. 6a), colorfully dressed pilgrims on their way to the temple of the village of Nandgaon

(figs. 6b and 6c), where they encounter a barrage of water and colored powder originally made of dried

flower petals. One cathartic moment happens when the women of the village of Barsana

beat men with long bamboo sticks (figs. 6d and 6e). Their attacks are meant to channel anger accumulated throughout the year. They

wear sāris (a garment made out of large sheet of cloth wrapped around the body) in bright colors

that are drawn across their faces, veiling their sight. The men protect themselves

by bandaging their head with cloth and by a colored shield (see fig. 6d). Throughout the film, the camera is often brought in at close range to the events

and is also made to reflect the view of those who are engaged in the celebration-as

seen in a take which (fig. 6f) shows what a man might see when kneeling in front of a woman and being beaten by

her. In this way, the chosen women are allowed to act out the reversal of Indian society's

established rules. The devotional paradigm behind this festival is one of finding

god beyond worldly forms, of play and of transcendence, and is thus "especially popular

among the low caste and low class."68 All these-partly powerfully performed-symbolically laden gestures, ceremonies, and

colors reviving the stories about Krishna and his companion Radha, together form a

semantic dimension that cannot be found in Oiticica's works. In the words of the curator

Manuel J. Borja-Villel we could perhaps say, his work is rather "a ritual without

myth, a ritual which enables the participant to discover and remake his own physical

and psychic reality."69 Oiticica is not consistent in his position towards myth, however; especially in the

1960s it remained an open topic for him.70 It is not the spiritual that marks the main difference between Holi and Oiticica,

as the artist provides numerous hints through which his works reveal their spiritual

dimension. It is the absence of enactments of mythical stories and customs, as well

as the impulse to experimentation which makes them differ.

6a).

Colored banners in the Holi Festival in India; b, c) camera shows closeups of pilgrims wearing colored clothes during their ascent to the temple of the village

of Nandgaon; d-f) veiled women of the village of Barsana (actually but symbolically)

beating men with long bamboo sticks. Filmstills taken from Beeche, Holi: A Festival of Color. A Hindu Celebration (vid supra n. 67).

Experimenting by Modeling (Ap)perception

In what does the experimenting with the Parangolés consist? It is important to acknowledge

that for Oiticica various levels of experimentalism exist, and he welcomes a broad

variety of kinds. However, all have to do with the body. "Oiticica's parangolés redefined corporeal experience from what a body is to what a body can do."71 What does one do as a body that experiments with experience and perception? Perhaps

one provokes a perception-related flowing together of colors, lights and structures

by straining the lenses of the eye and by testing all possible focus adjustments,

by constantly shifting the gaze so that a conscious fix on specific details is avoided.

This leads to a gorgeous setting, the movements of which are not foreseeable and arise

from several (inner and outer) sources. Moreover, the experience is one of time stretched,

lasting.72 Such an experiment in perception takes time, due in part to the fact that simultaneously

the conditions of the sensory impressions change continuously given the movement of

the fabric.

Art critic Sabeth Buchmann and cultural critic Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz write: "The

means employed to this purpose, however, have nothing to do with an aesthetic of overpowering

the viewer, which characterises the Minimal art, Op art, Pop art and multimedia art

popular at that time."73 On the one hand I agree with them insofar as Op Art differs from Oiticica's works

as-in the words of the artist-it reaches only the sensorial, not the supra-sensorial.

However, in order to get there, some degrees of letting oneself be overwhelmed (as

a means to an end, not as ultimate result) are useful. It may be true, as in Op Art,

that the essential happens exclusively over time and in the perception, as well as

in accentuation of these occurrences. However, the variability is rather limited because

the original is static. Oiticica's main objection against Op Art is yet another that

has to do with the difference in the activation of the participants. In substitution

and abbreviation of a more extensive study on Op Art, here I limit myself to taking

up the exhibition catalogue "The Responsive Eye" (1965) written by the curator William

C. Seitz.74 He reports on scientific debates and their preoccupation with the question whether

the optical "effects" that Op Art yields in the recipients are (more) of a psychological

or a physiological nature, that is whether they take place in the brain or in the

eye. This limited scope of the questions gives the impression that the "effects" are

conceived as passive experiences and not as results of human modulations. The change

of perception under the influence of mescaline and LSD is the only variation in the

sense of an intensification that is mentioned in this context. Thus, Oiticica's criticism

that it is mainly a stimulus/response-reflex seems justified.

I consider as simple "sensorial" problems those related to "stimulus-reaction" feelings,

conditioned "a priori," as occurs in Op-art [...]. But when a proposition is made

for a "feeling-participation" or a "making- participation," I want to relate it to

a supra-sensorial sense, in which the participator will elaborate within himself his

own feelings which have been "woken-up" by those propositions. This "wake-up" process

is a supra-sensorial one: the participator is shifted off his habitual field to a

strange one that wakes up his internal fields of feeling and gives him conscience

of some area of his Ego, where true values affirm themselves.75

Oiticica declares his pieces as being "open" and "cosmic" works. He wants "the spectator

to create his own sensations from it, but without conditioning him to that and the

other sensation."76 Faced by reflex-like reactions, open works would not exhaust their full potential.

For that to happen another attitude of reception is necessary:

In my propositions, I seek to "open" the participator to himself-there is a process

of interior expansion, a dive into the self, necessary for such a discovery of the

creative process-action would be the completion of it. Everything is valid according

to each case in these propositions, especially the appeal to the senses: touch, smell,

hearing, etc., but not in order to "investigate" them through a stimulus-reaction

process, purely limited to the sensory, as with "Op Art." By proposing and indicating

an interior expansion within the spectator, it already aims at the supra-sensorial.

Supra-sensorial stability would be represented by hallucinogenic states (with or without

hallucinogenic drugs, since supra-sensorial life-experience of various kinds also

lead to a similar state; drugs would be the classic exemplary state of the supra-sensorial)

and, to complete the polarity, the complementary state, in other words, the non-hallucinogenic.77

As a first step, the open arrangement should meet participants ready to open themselves

up and as a second step it should make this openness productive. In the following

pages I will attempt to portray more vividly what kind of "perception work" the artist

links to creativity. I would like to make it clear that it is not my intention to

turn Oiticica's art into something pathological.

Suppressing the Protection Against Stimulation

In the framework of psychoanalytical traumatology, Sigmund Freud described the "stimulus

barrier" (Reizschutz) as a defense mechanism of the individual against stimulation from the outer world,

which secures that the incoming excitation magnitudes "will take effect only on a

reduced scale."78 Recent psychology uses the expression "latent inhibition" for the instance of the

preconscious sorting of impulses assessed as being irrelevant (due to former perceptions).

For a long time a weak filter mechanism was restricted to psychopathological findings

(schizophrenia).79 Psychologists Shelley H. Carson and Jordan B. Peterson offer yet another interesting

perspective for this context. They looked at the possible connection between latent

inhibition, the personality trait "Openness to Experience,"80 creativity, and intelligence quotient. They found out that under some conditions

a reduced filtering of stimuli can become productive. "The highly creative individual

may be privileged to access a greater inventory of unfiltered stimuli during early

processing, thereby increasing the odds of original recombinant ideation. Thus, a

deficit that is generally associated with pathology may well impart a creative advantage

in the presence of other cognitive strengths such as high IQ."81

Intoxicants can also provoke the overstimulation of the nervous system or the irritation

of the stimulus barrier.82 Such more global measures may exist alongside local ones. A bit too much happening

simultaneously helps one to let go, fostering the by-passing of the normal mode of

proceeding and, for example, facilitating the deliberate direction of the attention,

not as focused (as normal), but directed to all directions in order not to exclude

anything.83

Dimming Out Identifying Automatisms

A broadly dispersed attention span-provided that this can be controlled consciously-is

in itself already an unconventional attitude. Yet another special feature can be added.

What is searched for is an instance of the visual or the multi-sensorial which would

correspond to the neologism "olfactic". With B 50 Bag Bólide 02 "Olefactic" (1967) Oiticica invited the participants to smell freshly ground coffee. The poet

Waly Salomão writes insightfully: "The olfactic precedes the Olfactory, which only

exists as a mediating discourse. Olfactic is a direct sensation, en train de se faire, immediate."84 The immediateness, presence, and processual nature are emphasized. What can a direct

visual sensation before any conceptualization be called? How can we release seeing

from being oriented towards object identification? Possibly by concentrating exclusively

on the sensual characteristics? Pure primordial perception is not easily attainable.

Some clues that it is worth trying can be found in Oiticica's writings, such as in

his "Notebook Entry on Bólides":85

Clearly, earlier perceptions cannot be erased, although, through a new aesthetic experience,

the new perspective will be heightened, allowing for extraction of new possibilities

from an object or a given solid form. I repeat that this is only possible in the aesthetic

transformation of the object, which for me takes place in the line of color and its

transformation into "symbolic form." It is the interior aesthetic renewal of our wasted

world of everyday objects.86

Assuming an unconceptualized perception is at all possible, it would be interesting

to know how much overload is necessary for it to happen. Overload is something experienced

by all who see for the very first time because they still have a learning process

ahead of them before their sight "normalizes." Reports about the first optical perceptions

of formerly blind persons who regained their eyesight after surgery are rare and hotly

debated.87 Although studies address advances in identity learning, object recognition, form

discrimination, distance determination, and allude to what could not yet be attained,

they seldom provide detailed information about the actual impressions (indeed, how

would one capture the experience in words?). Apart from a Russian study from the 1950s

that reports the case of a girl who lost her eyesight during early childhood and could

thus name colors, and who had her eyesight restored, for example, describes something

"big, red, and white";88 whereas in other studies the impressions are described with emotionally laden and

moreover hardly revealing adjectives such as "confusing"89 or "nasty."90 In the beginning, blind individuals who see for the first time often go through a

difficult period of disorientation, insecurity, and, subsequently depression. Under

these circumstances the impressions frequently receive a negative connotation and

thus it is all the more surprising how the art historian Michael Baxandall comes to

his positive formulation: "Its inquietude and movement [of the visual array as a meaningless

field of colours] are simply rewarded with the pleasure of lively and changing stimulation."91 Such a positive connotation of the stimuli to be incorporated is what we have to

think of with respect to Oiticica's proposals. According to my hypothesis, in sighted

people a kind of overload has to be artificially induced. It is easier to dedicate

oneself to non-identifying seeing, to practicing a momentary visual agnosia ("difficulty

in recognising common objects from vision"),92 and to maintain it for a while when confronting abstract forms that undermine the

sensing thresholds and that function immersively-invasively. The body is then completely

busy with broadly opening itself in order to give preference to the reception of unbiased

impressions and to exclude the normal automatic process of categorizing. What is to

be filtered out is not the sensory richness of the impressions, but the apperception.

It is not about a refusal of (a negatively connoted) apperception in so much as it

is an evasion of attentive perception (as the novelist Heimito von Doderer would conceive

it),93 but about a perception-related inventive exploitation of the "openness" of Oiticica's

work proposals.

Training a Perception Aimed at Openness

An analysis of the group of works known as Parangolés which Hélio Oiticica developed

offers possibilities for a better understanding of creative expression as directed

toward the participant himself/herself. In his writings, the Brazilian artist links

the supra-sensorial to political maturity and self-determination. This contribution

investigates how this idea manifests itself; or better: is instantiated in the work

complex of the Parangolés. They can be seen as instances for training a perception

aimed towards openness and creativity instead of towards object recognition (repetition

of the known). It is about actively seeking, exploring, and enjoying an overwhelmingly

rich self-made stimulus. The kind of interactivity that leads to such high claims

bears moments of experimentation and playfulness but is demanding as it asks for full

self-investment. Thus, there is a major-often overlooked-difference between acting

from inside a Parangolé and observing someone engaged with it from the outside.94