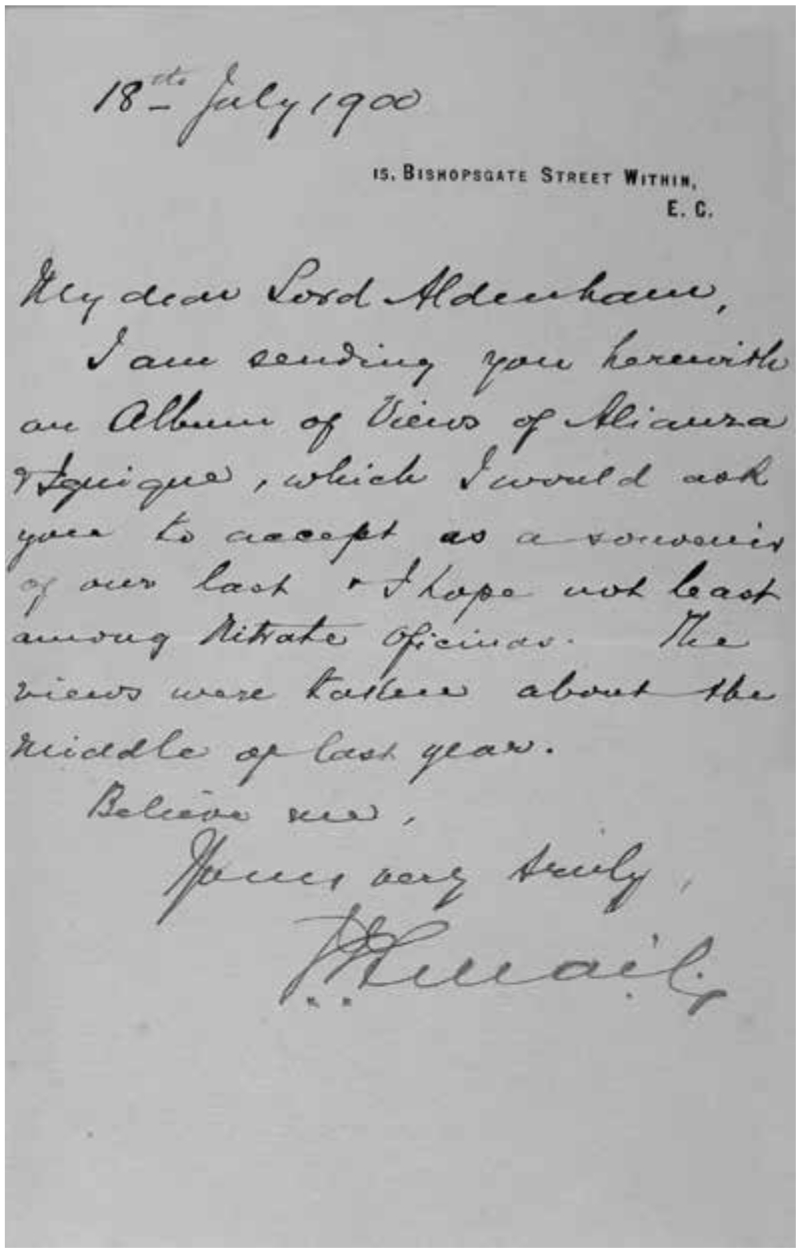

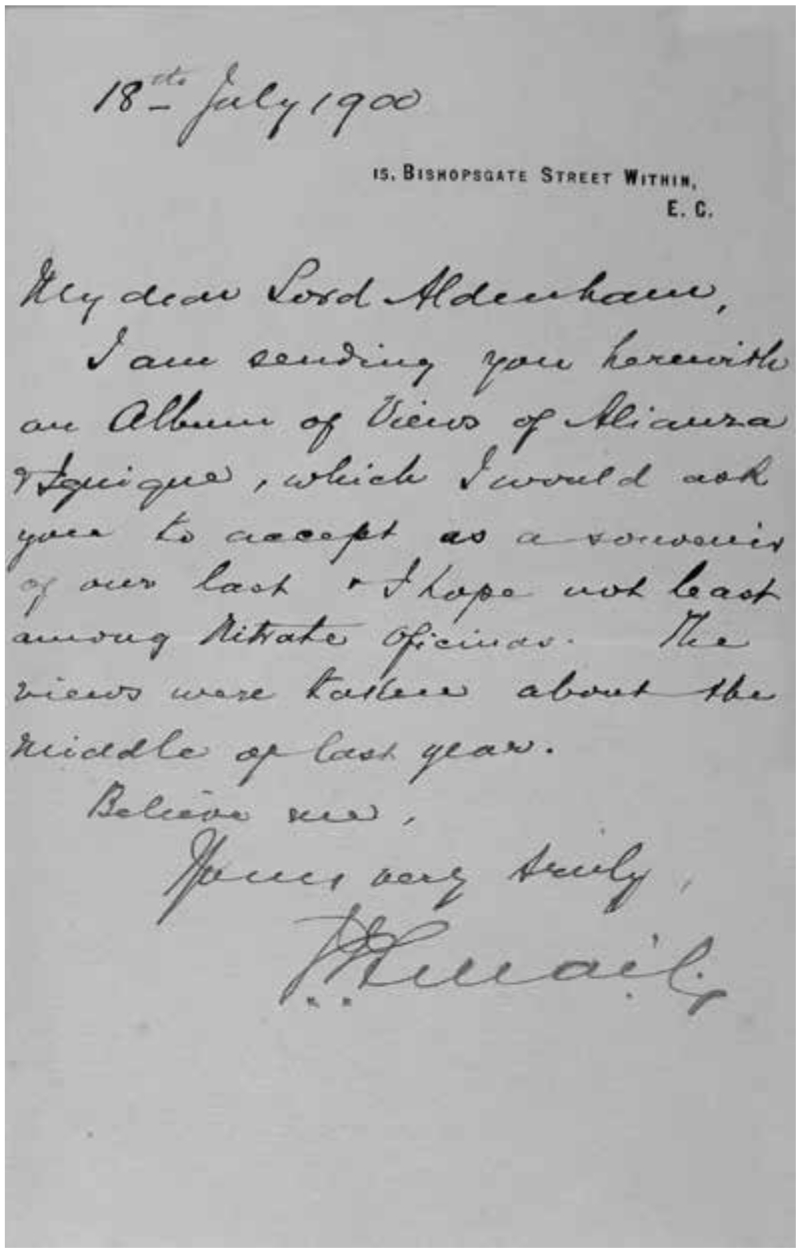

On 18th July 1900 Mr. Smail wrote to Henry Hucks Gibbs. He addressed him by his title:

I am sending you herewith an album of views of Alianza Iquique, which I would ask

you to accept as a souvenir of our last but I hope not least among of Nitrate Oficinas.

The views were taken about the middle of last year1 (Fig. 1).

1.

"Letter to Lord Aldenham from Mr. Smail," 18th July 1900, in Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899, album 12, Fondo Fotográfico Fundación Universidad de Navarra/ Museo Universidad de

Navarra, Pamplona.

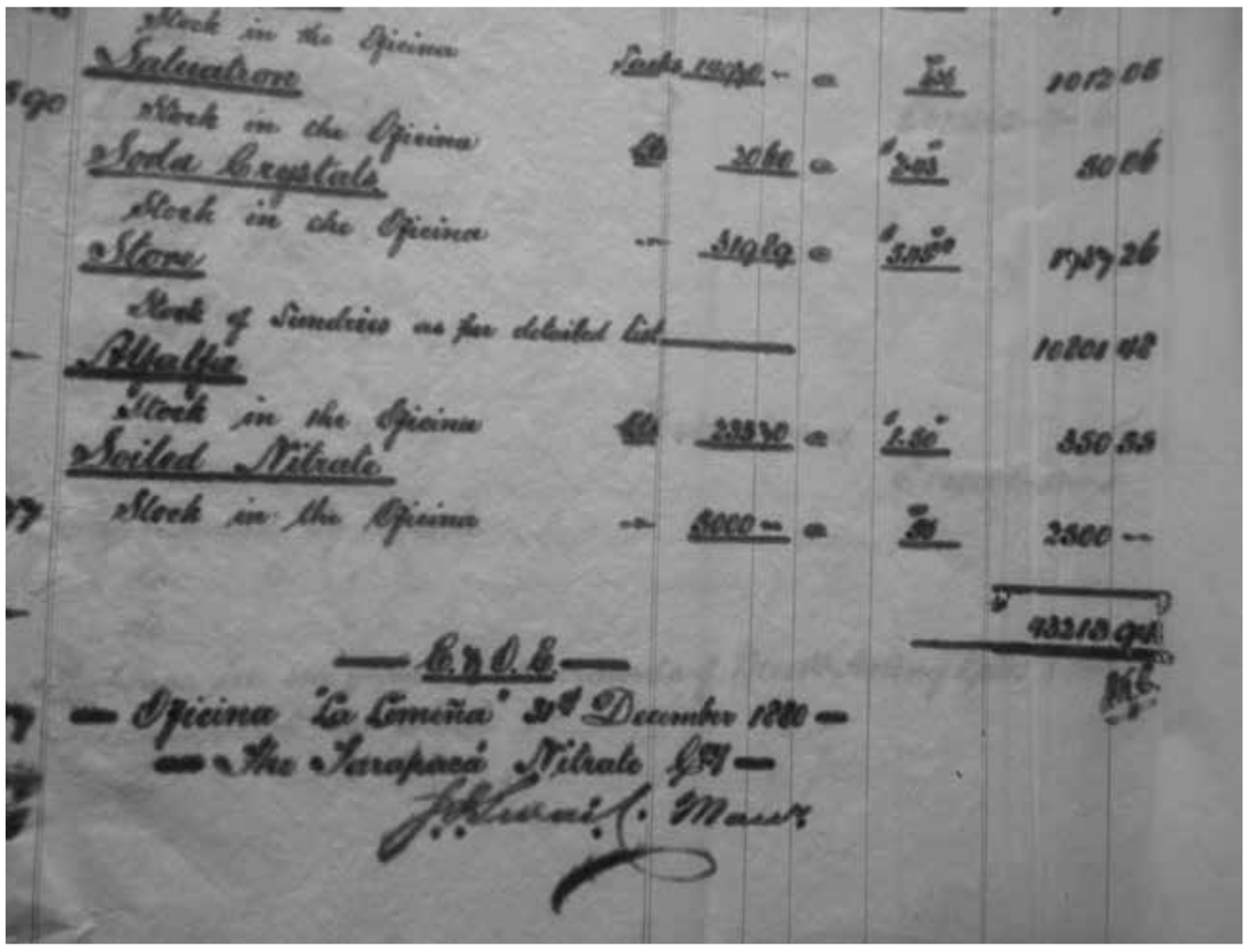

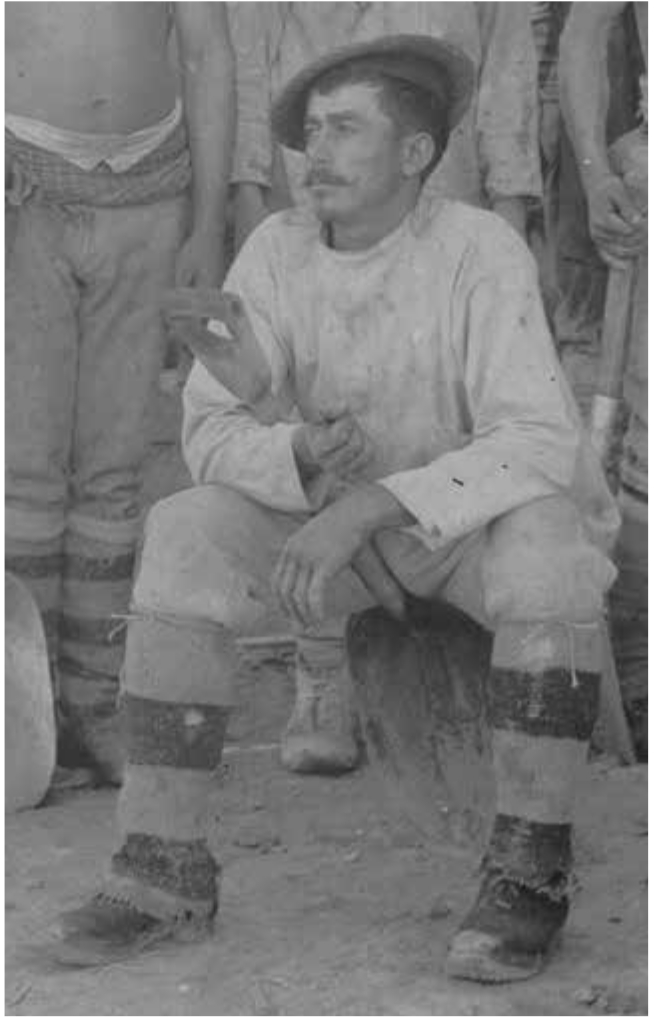

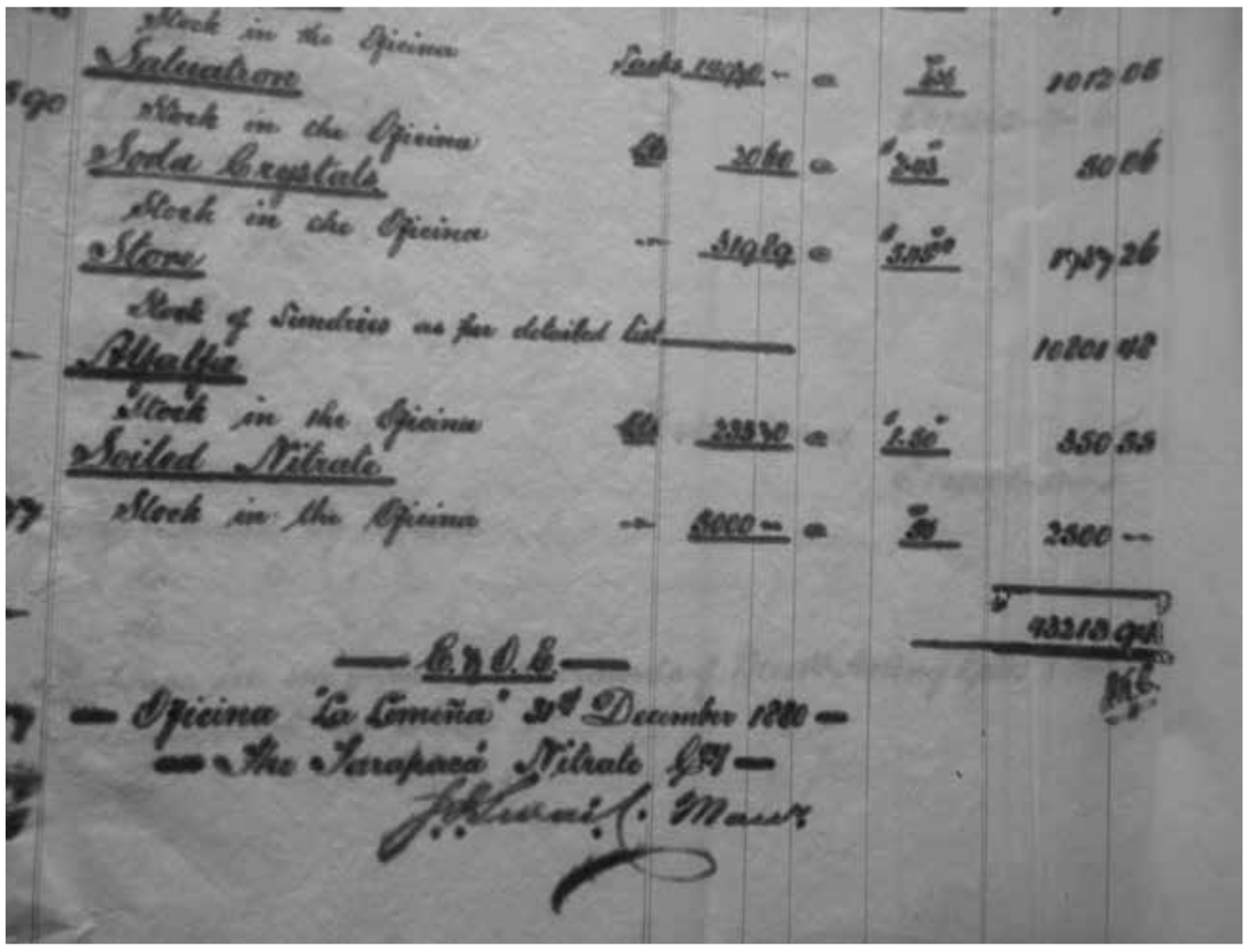

Mr. Smail was a manager of nitrate companies mining in Chile owned by merchant house

Antony Gibbs and Sons; he was accustomed to corresponding with their London office,

sending financial accounts to the head of the house (Fig. 2).2 The "Album of views," which has the title Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 embossed on its cover, contains around 90 photographs of the nitrate industry in

the Atacama Desert of Chile, concluding with panoramas of the nitrate ports. The desert

was intensively mined for nitrate from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth

century. The industry was driven by British capital and investors that colonized an

inhospitable place, an almost waterless environment. Machinery was imported from Britain

and men to labor, Chilean, Bolivian and Peruvian, were brought and bound through an

enganche system to live in the nitrate Oficinas.3

2.

Manager's Report, Tarapaca Nitrate Company, Antony Gibbs and Sons Limited, London

Metropolitan Archives.

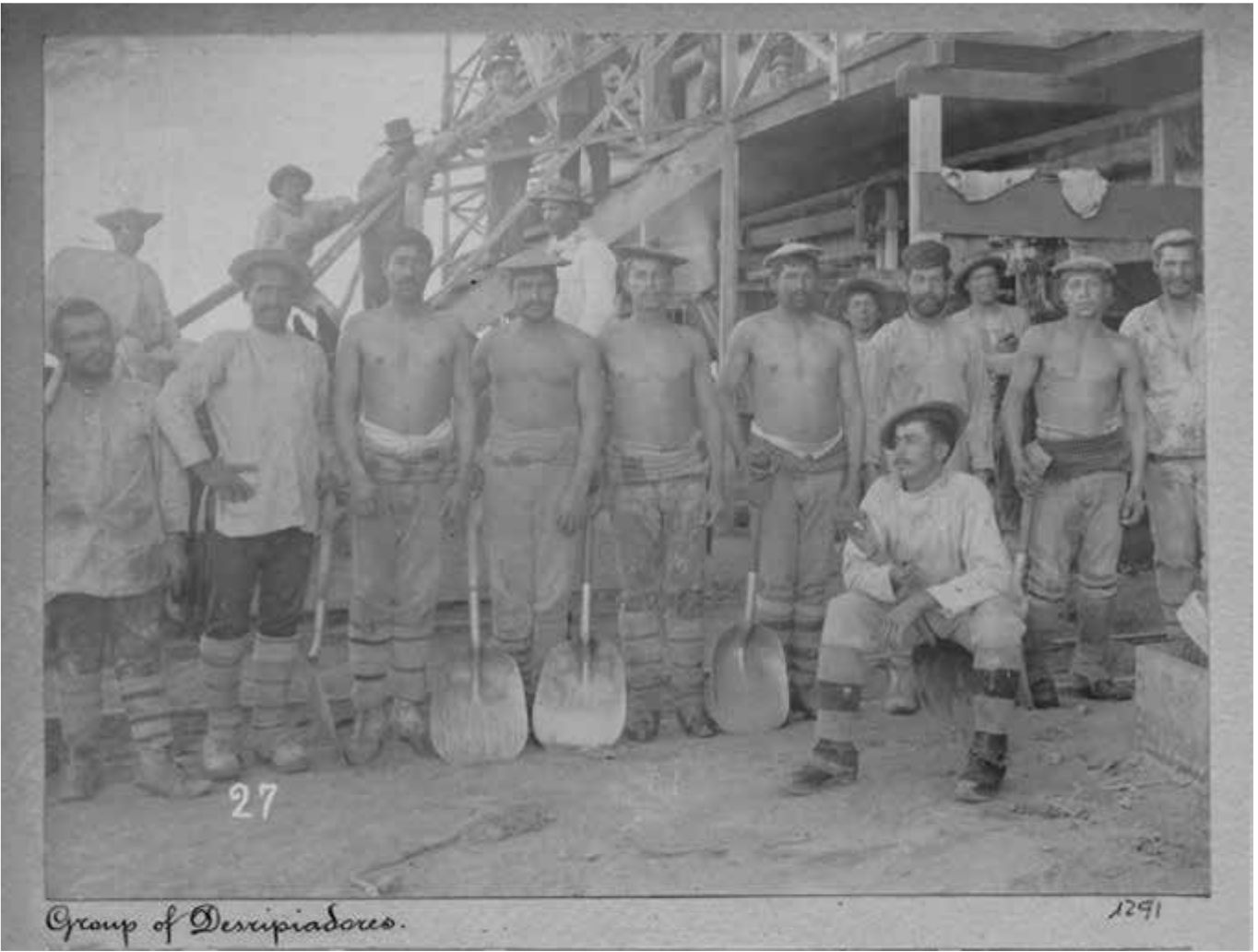

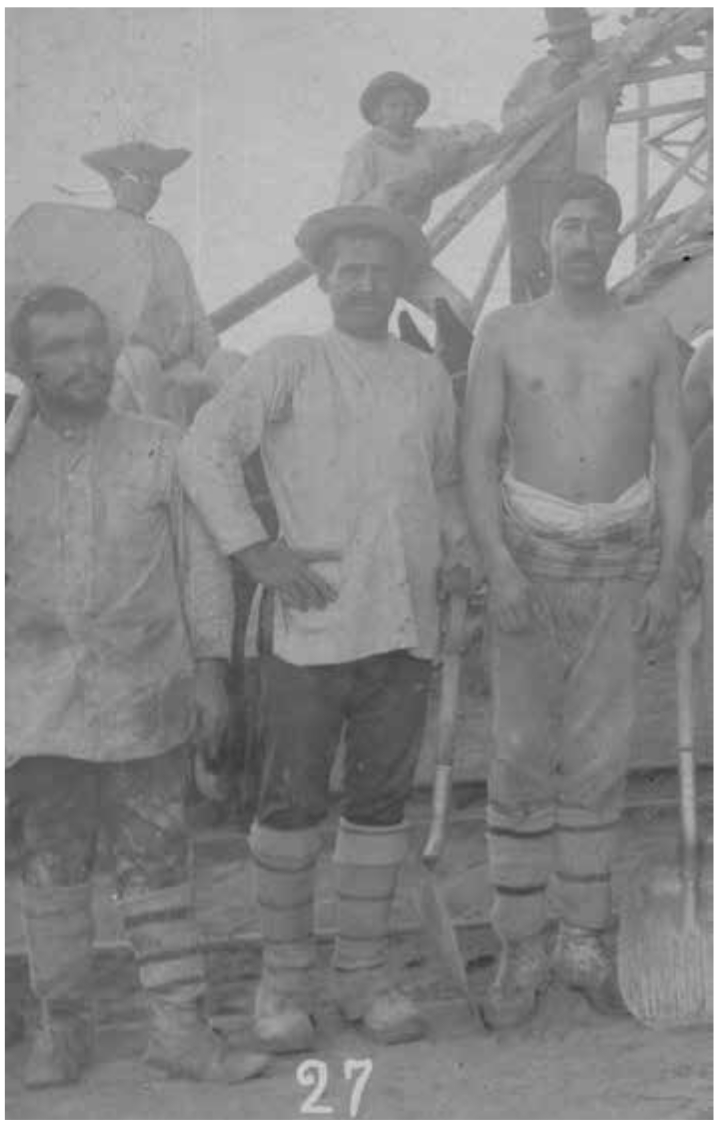

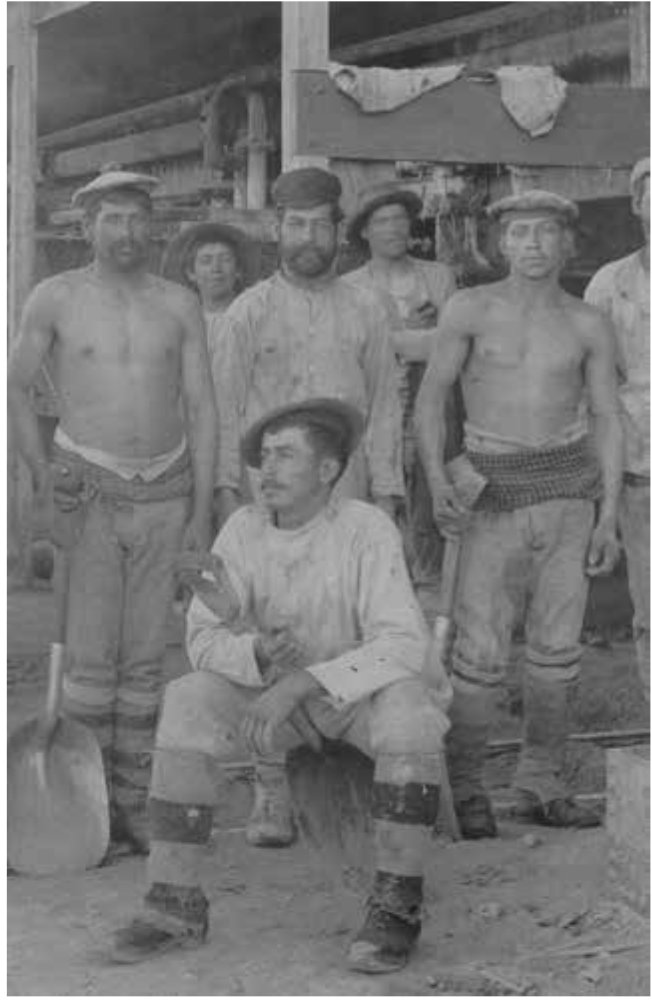

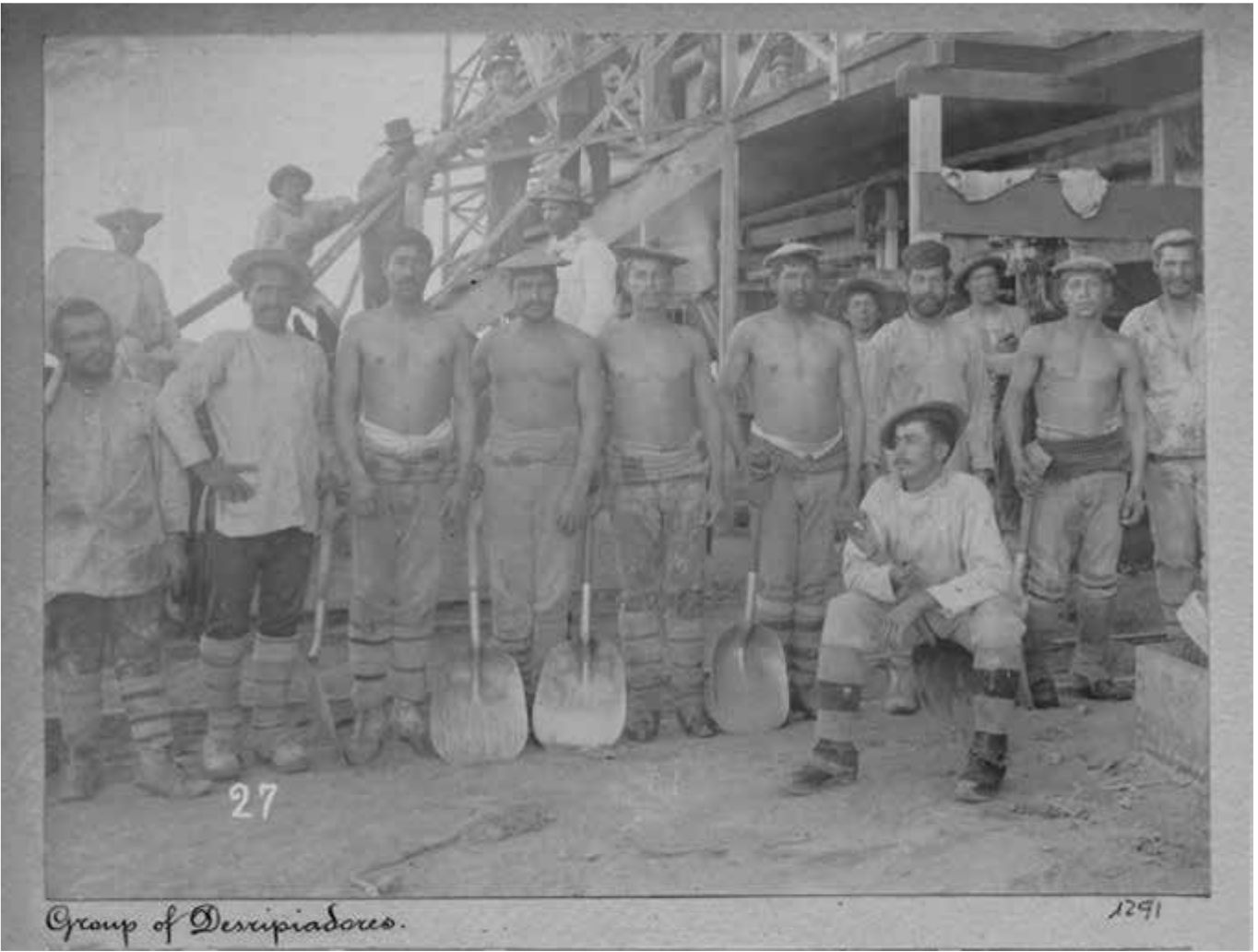

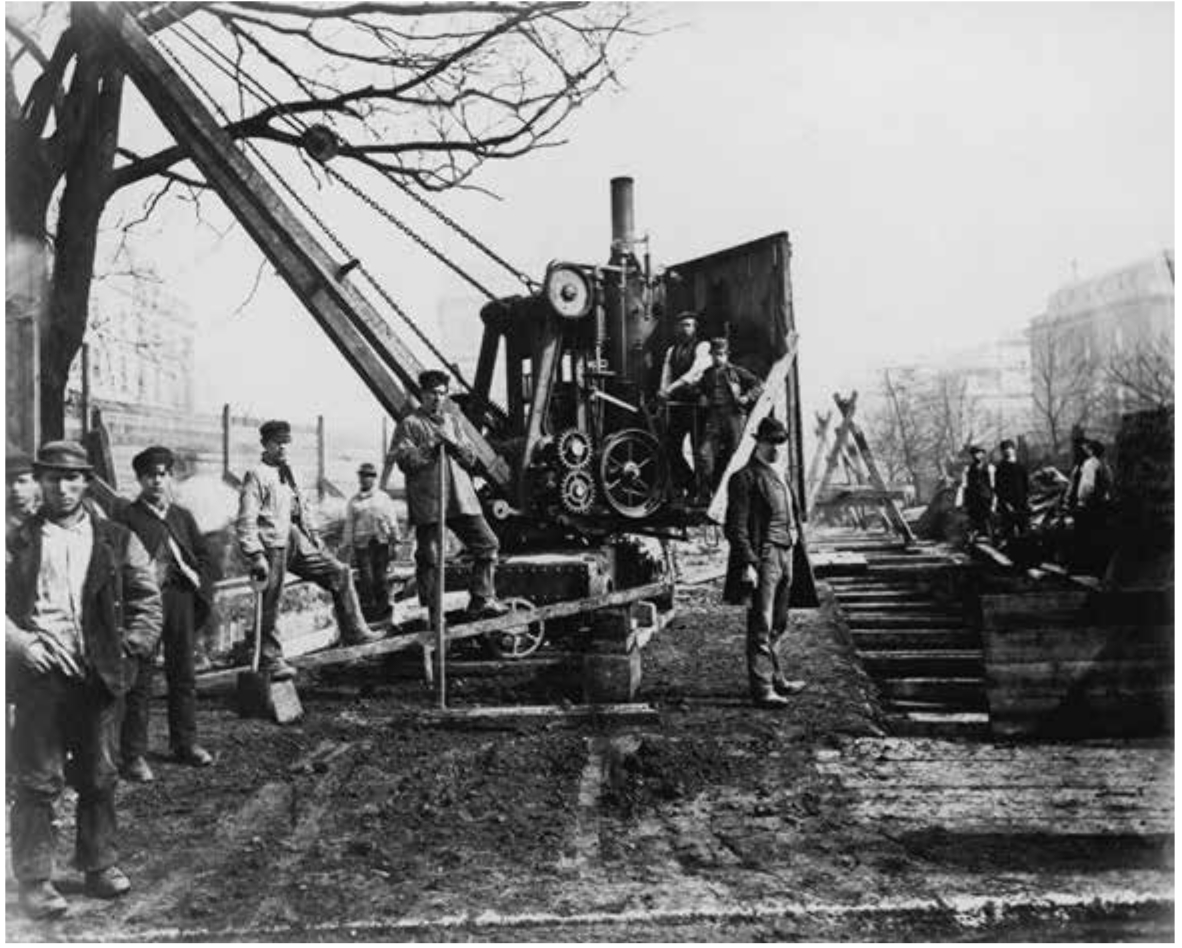

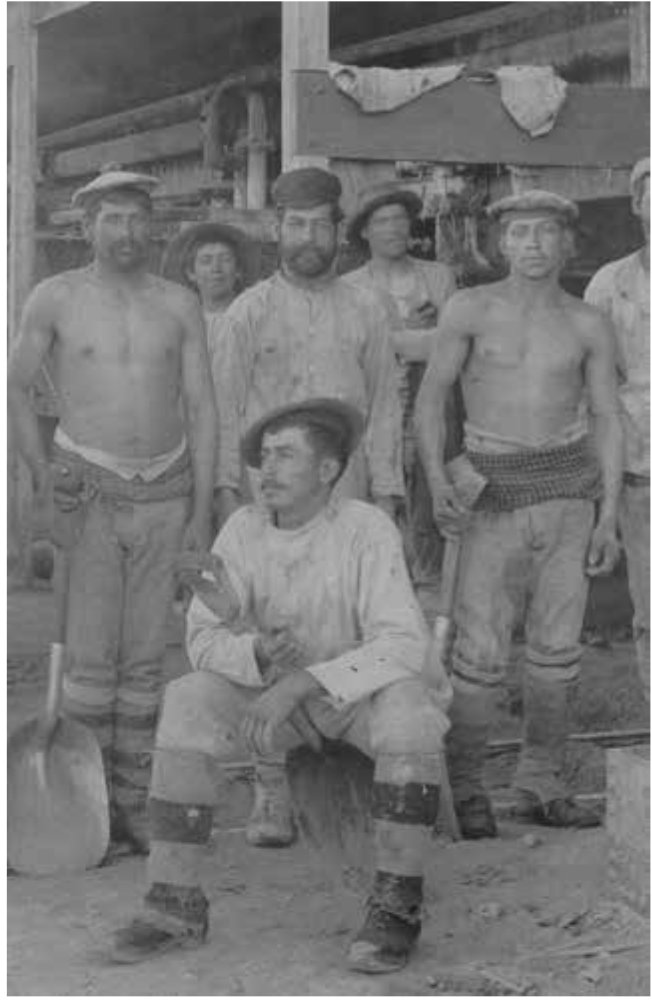

The Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 album contains one image of contemporary political significance: the photograph numbered

27 (Fig. 3) presents a row of nitrate miners, shovels in hand, entitled "A Group of Desripiadores";

it has been deployed in commemorations of the Escuela Santa María massacre, when the

killing of hundreds of striking nitrate miners, railway workers, cart drivers and

artisans by government troops took place in Iquique on 21 December 1907. A week before,

5,000 nitrate workers had walked from the oficinas along the railway lines that cross the pampa to rally in Iquique; they waited in

the large courtyard of a school called Santa María while their representatives, including

José Briggs and Luis Olea, presented their demands: an end to payments in fichas, the nitrate company tokens that were the currency of the overpriced company stores;

wage stability with the establishment of an eighteen pence peso; safer working conditions, especially around cachuchos, the mechanism for crushing caliche, the desert rocks containing nitrate; honest working practices, particularly an end

to processing the low grade caliche for which workers had been refused payment; more schools and free evening lessons

for workers; an amnesty for strikers. The nitrate companies, merchants and bankers

refused to negotiate. Regional Governor intendente Carlos Eastman declared a state of siege and ordered nitrate workers back to the

pampa. When they refused, the military, led by General Silva Renard, used machine

guns to fire on the strikers and then charged at them with mounted troops and bayonets.

"Iquique, site of the greatest labour uprising, remains part of the class consciousness

of militant labourers" writes Michael Monteón.4 The Santa María massacre is, summarizes Lessie Jo Frazier, "the central symbol of

repression that led to the formation of working-class consciousness."5 It has been commemorated with annual rallies at the school and, most importantly,

recalled in song. The Cantana Santa María of Iquique was written and popularized during the 1970-1973 Popular Unity period. The 1907 killings

became a more complex symbol of class struggle in Chile: "an allegory for the overthrow"6 of Salvador Allende's government by General Pinochet with his United States supporters.

3.

"Group of Desripiadores," in Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899, no. 27.

The figures of nitrate workers photographed some eight years before the Santa María

massacre are an embodiment of the heroism of manual labour, collectively organized.

Their forms circulate far beyond their position in the Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 album;7 they have been remodelled in metal, digitally reproduced on Left radical blogs as

well as used to represent the regional history of Iquique to tourists (Fig. 4). The image is arresting (Fig. 3); it offers the possibility of catching a glimpse of the work behind nitrate mining,

of the experience of shovelling the desert earth, of the material conditions of laboring

in the desert: a flash8 of a past reality. It contains, in Walter Benjamin's words, a "tiny spark of contingency":

No matter how artful the photographer, no matter how carefully posed his subject,

the beholder feels an irresistible urge to search such a picture for a tiny spark

of contingency, of the Here and Now, which reality has so to speak seared the subject.9

4.

Box of Biscuits from local Iquique shop, 2012.

Maybe. Hopefully. We shall see. This analysis examines the Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 album as a fragment of an archive of the British nitrate industry in Chile. I offer

a reading of its sequence of photographic images. Space allows pausing upon only a

few of the 90 images to consider photographic practices used to record the mining

exploitation of Atacama Desert.10

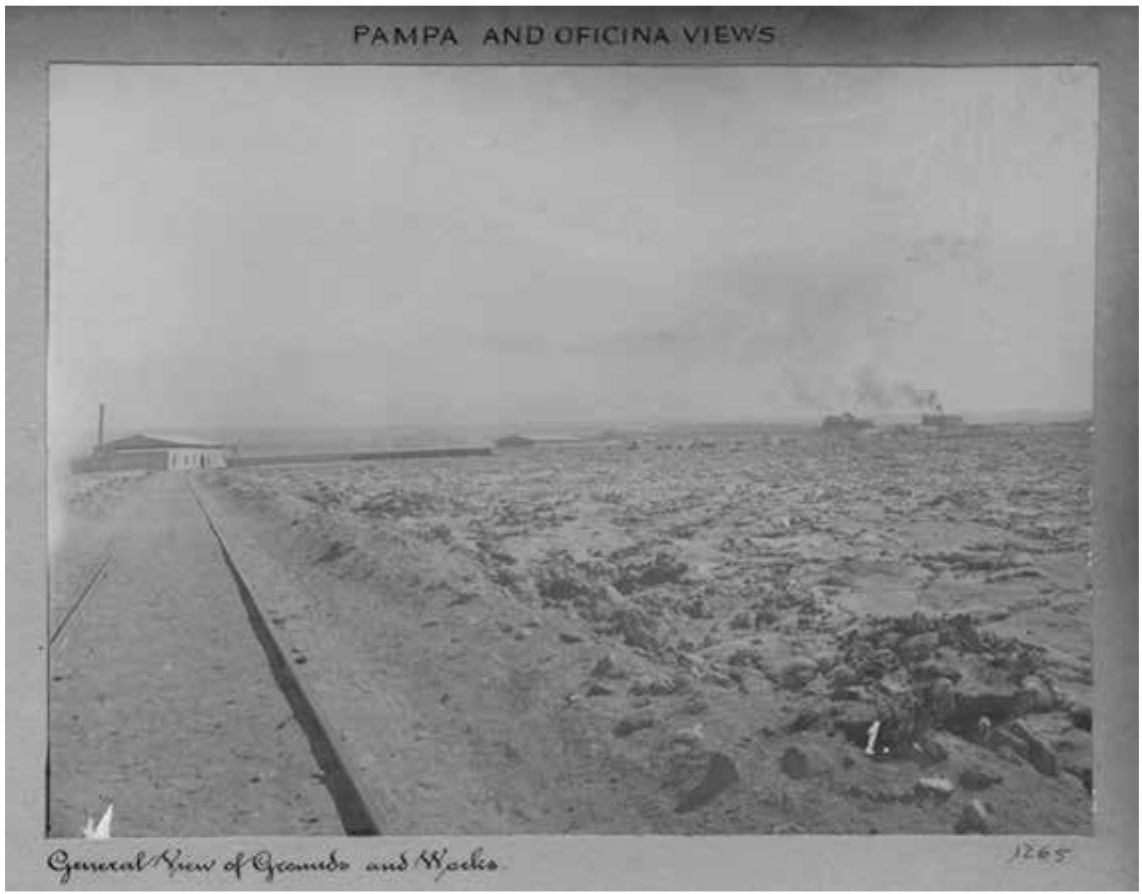

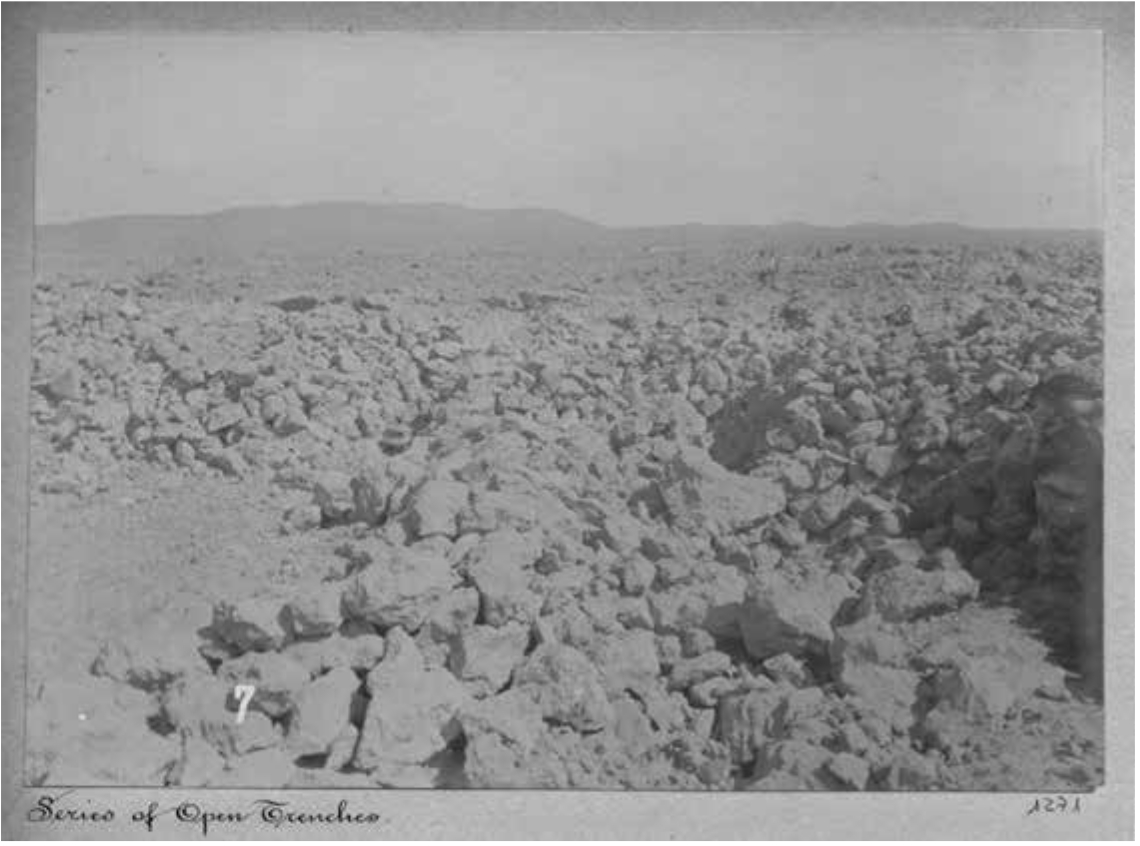

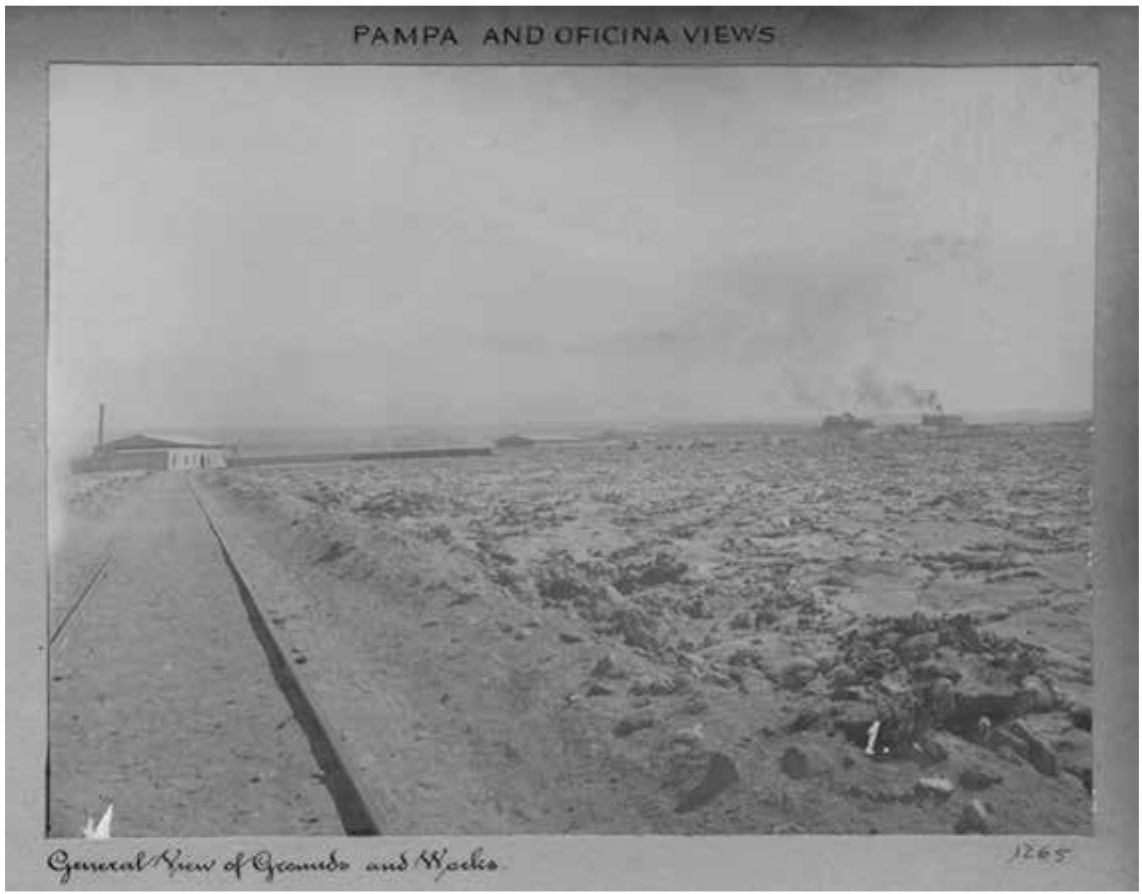

The first image, the number 1 scratched onto its surface, is, I would suggest, one

of the most important of the album (Fig. 5). Initially, it might appear rather blank: an empty sky, pale sepia produced by colodion

printing process, hangs over a flat desert, which is only a little darker in colour.

The rocky surface creates some shadow. The nineteenth century camera has captured

details of surface. The earth has texture but, with its emptiness, the sky moves to

the foreground beneath and below it. The railway tracks established lines of perspective

along the left of the image; the right hand track, a long straight line with a dark

sharp shadow, propels the viewer towards a building and then a wall. Also distinguishable

because its shape is darker, straighter than the surface of the desert, a wall cuts

across the horizon where the desert fades into the sky, providing another line of

sight through a series of structures that continue to draw the viewers attention across

the image towards a distant factory building. Entitled "General View of Grounds and

Works" (Fig. 6), the image prepares the viewer for the following 90; it sets the scene, indicates

everything that is in store.

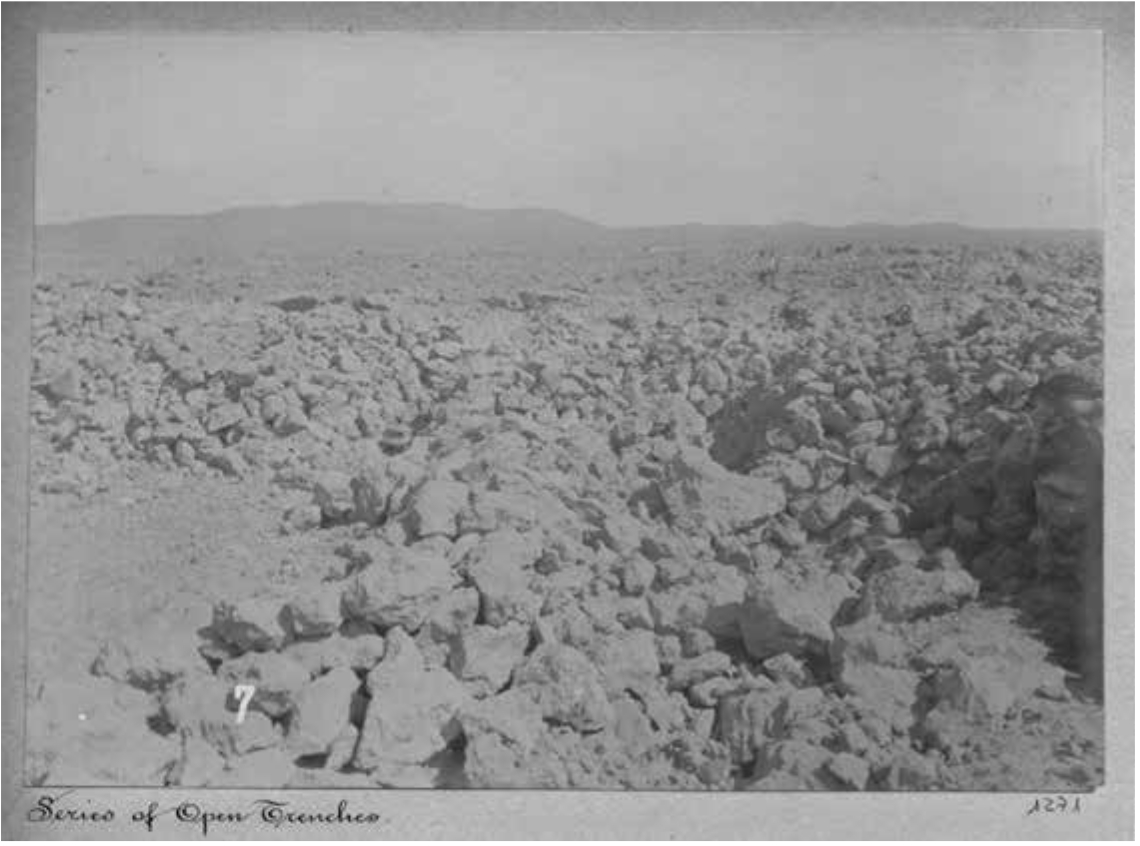

5.

"Series of Open Trenches," Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899, no. 7.

6.

"General View of Grounds and Works," Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899, no. 1.

Rather than blank, the empty, flat image is full and quite dynamic. The railway tracks

generate a geometrical order; the lines square off the desert. The view's photographic

arrangement posits an industrial topography; it shows a worked and controlled landscape.

Within a measured boundary, the desert's uneven surface becomes a nitrate field, one

of the "Grounds" of industry, to use a word taken from the image's written title.

Tracks and walls are furthermore, lines of movement, visual and geographical trajectories.

Their destination, on the far right of the horizon is the Oficina. Its smoking chimney,

a sign, or more precisely, an index of industrialization (Fig. 6). The viewer's visual path simulates that of the train, on which the photographer

carrying his camera and other photographic paraphernalia would certainly have travelled.

Train and photographer, with those who have flicked through the album trailing behind

them, are heading for the Oficina. The opening image promises a journey and, indeed,

a journey does unfold through the album.

The first 40 photographs trace the mining, processing and transport of nitrate; its

transformation from desert rock, a mineral deposit, caliche, lying just beneath the surface, to a chemical, bagged and ready for transport (Figs. 7 and 8). As nitrate changes its material state, it crosses the landscape: each photograph

shows an industrial stage and is a geographical frame. When the nitrate is loaded

onto the train to leave the desert (Fig. 8), the camera's movement and the viewer's gaze behind it, rest on the Oficina itself.

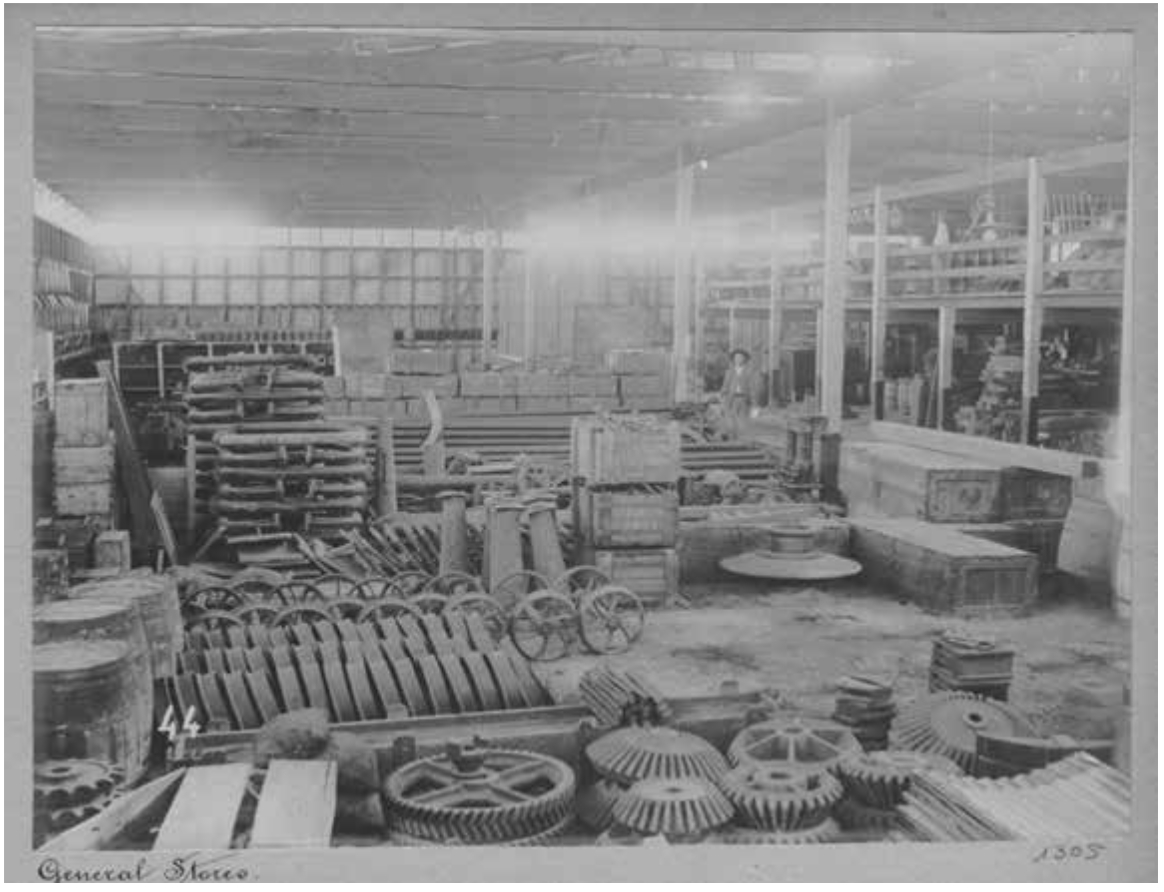

A tour of the nitrate works and nitrate town in 20 photographs opens with a view of

the general stores and concludes with one of the administrator's house (Figs. 9 and 10). This sequence is an interlude. The image that immediately follows, the selection

of which seems to use editing techniques that characterised early moving film, shows

the arrival of the train pulling sacks of nitrate to the port of Iquique (Fig. 11). It is as if the nitrate town tour took place while the bags of nitrate were travelling

across the desert to Iquique. Geographical frames are also time frames. When the train

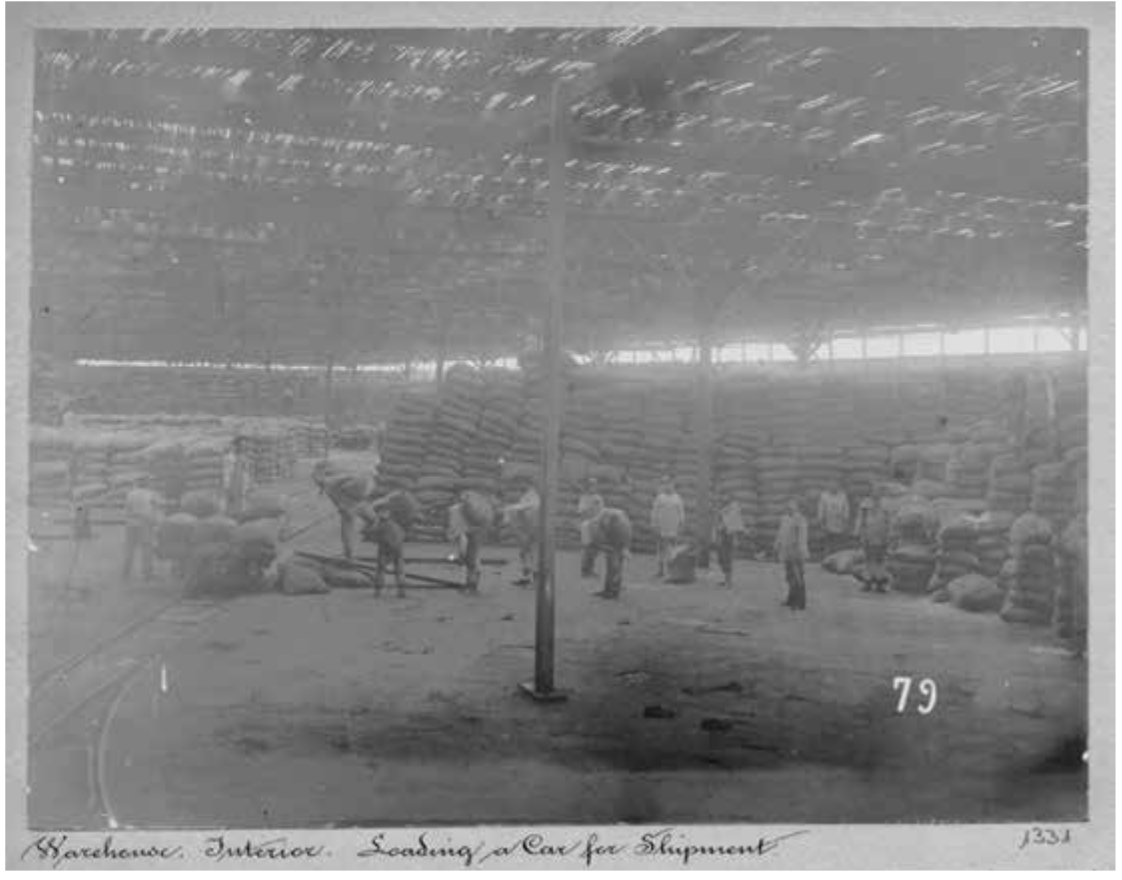

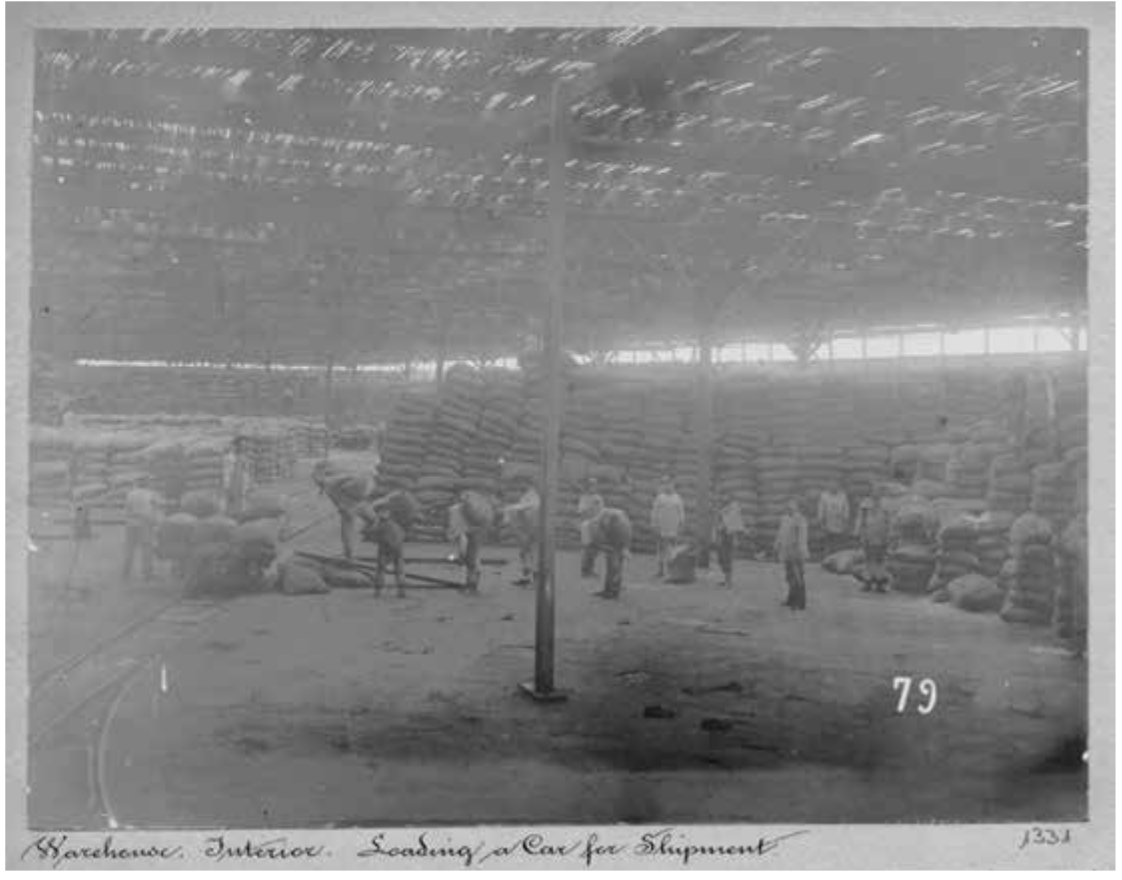

enters Iquique, the viewer joins nitrate's journey. The next sequence, ten or so photographs,

tracks the movement of nitrate as it is transferred from vehicle to vehicle, stack

to stack, from train to warehouse, warehouse to dock, boats to ships (Figs. 12 and 13). Here is evidence of its export, a measurement of the quantity of nitrate. The effect

of the images is cumulative: piles upon piles of stock are a display of abundance,

always a representation of wealth.

7.

“Loading Trucks for Transport to Iquique,” Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899, no. 39.

8.

“Leaving Works for Port,” Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899, no. 40.

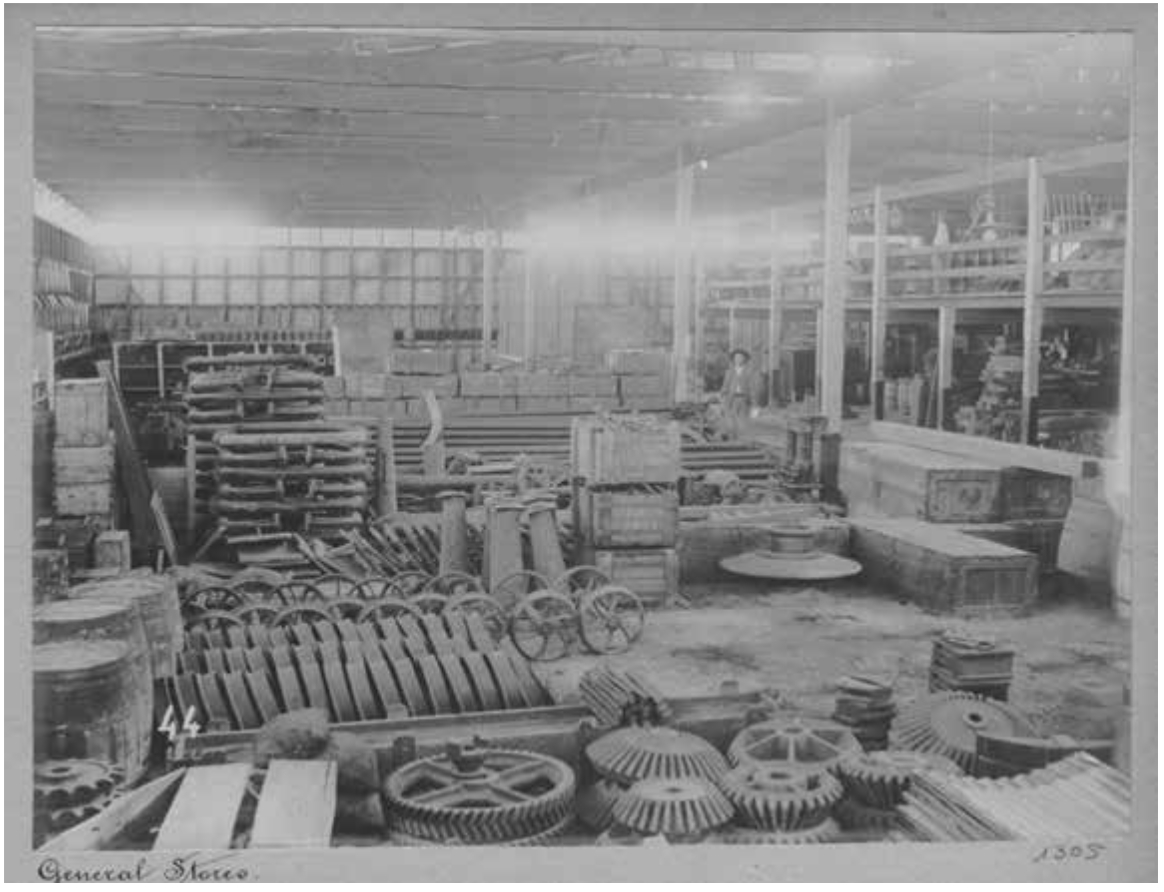

9.

“General Stores,” Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899, no. 44.

10.

"Exterior of Administration House," Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899, no. 71.

11.

"Arrival of Nitrate Train in Iquique," Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899, no. 76.

12.

"Warehouse Interior. Loading a Car for Shipment," Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899, no. 79.

13.

"Pier for shipping Nitrate into Lighters," Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899, no. 81.

The album Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique presents a photographic sequence that is spatial, material and temporal: from the

desert to the sea, from rock to commodity. Furthermore, there is an evocation of historical

time within the sequence that makes industrial process appear as historical progress.

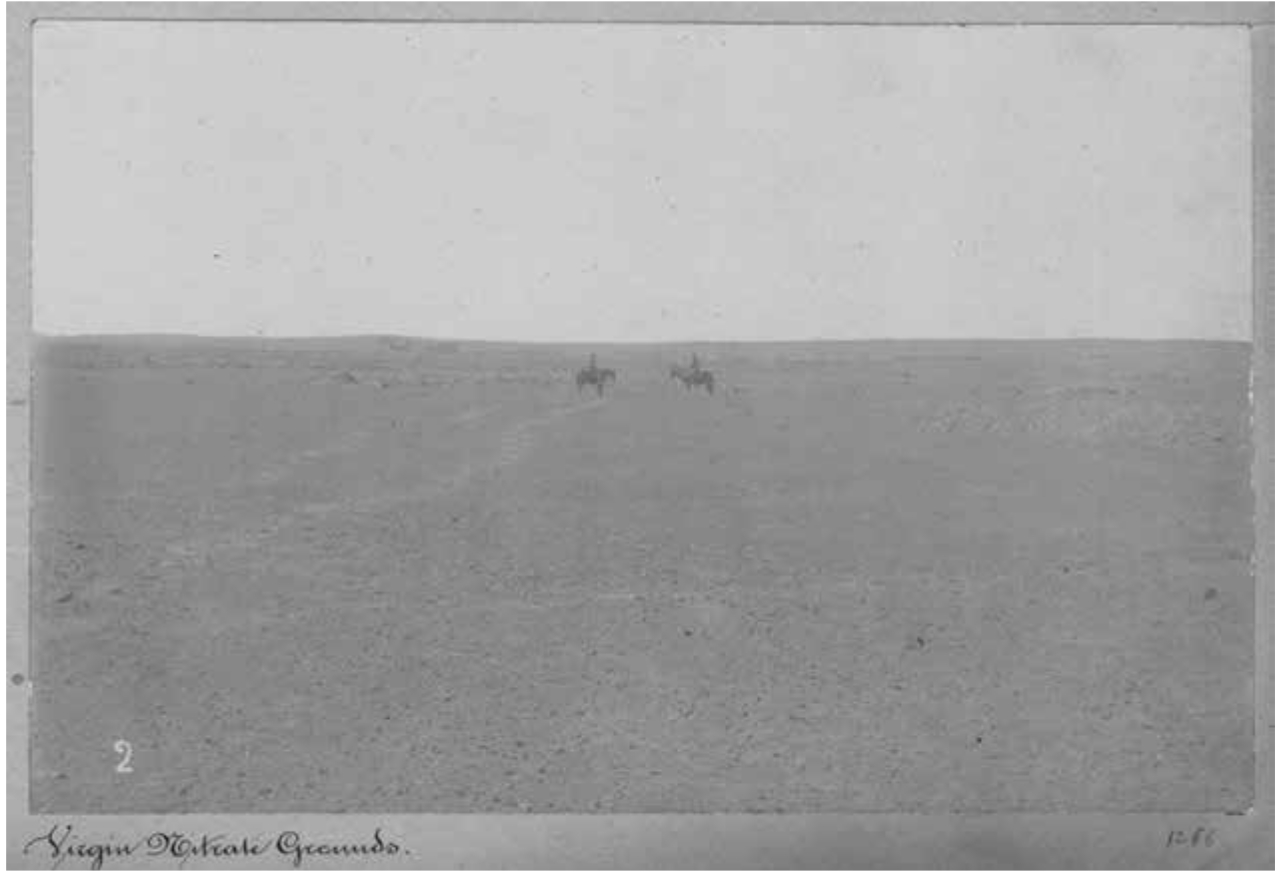

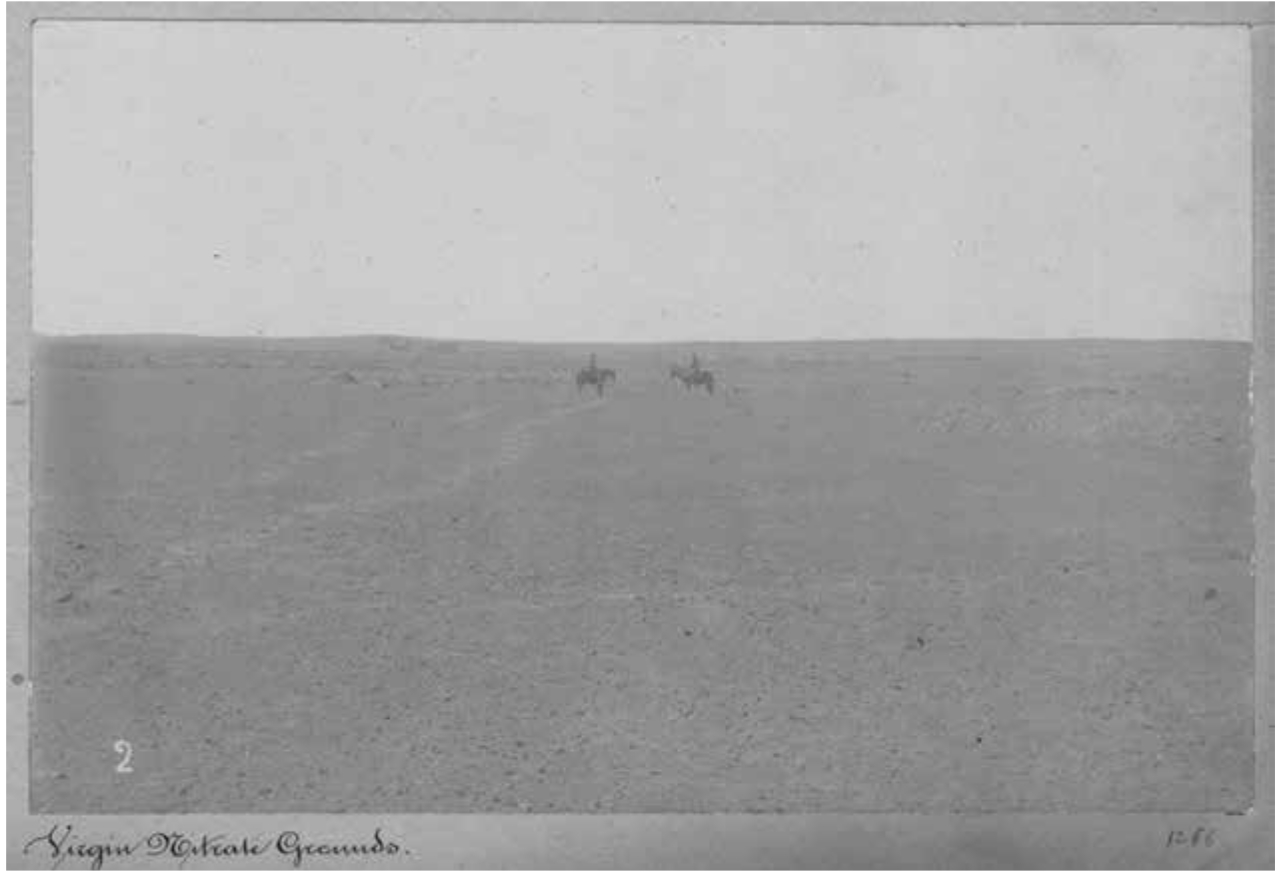

It is the second image of the album-that which immediately follows the opening photograph

of a worked controlled desert landscape, an industrial topography- which opens the

historical sequencing. Entitled "Virgin Nitrate Grounds," it is almost featureless,

a photograph of nothing, no event, no action (Fig. 14). It consists of two blocks of colour: a pale earth and an even paler sky. It displays

the desert as vast empty expanse, an uninhabited land, waiting for something to happen.

The human figure is scaled small against the desert to demonstrate its emptiness and

readiness. Two men on horses are positioned in the centre of the photograph; their

forms are indistinct; only an outline is discernible. The horses are held (one by

the reins) facing each other, angled to form a gateway into the desert vanishing to

a point between them. Across from each other, the men look into the distance. The

profile of their clothed bodies, the shape of their hats not their faces visible,

indicates they turned away from the camera, encouraging the viewer to gaze as far

as their eyes can see, to the vanishing point. The undisturbed surface of the empty

desert spreads out before them. In this geographical time frame, there is no smoking

chimney, no signs of industry. In the photographer's time, real time, if you like,

he has simply pointed his camera away from the Oficina Alianza, the fully operational

Oficina, that he was heading towards as he travelled on the train. He has produced

another view of the desert seen as the Oficina's past; thus his sequencing of photographs

becomes an account of the desert's industrialisation; it shows the industrial transformation

of the Atacama desert as a historical as well as daily operation.

14.

"Virgin Nitrate Grounds," Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899, no. 2.

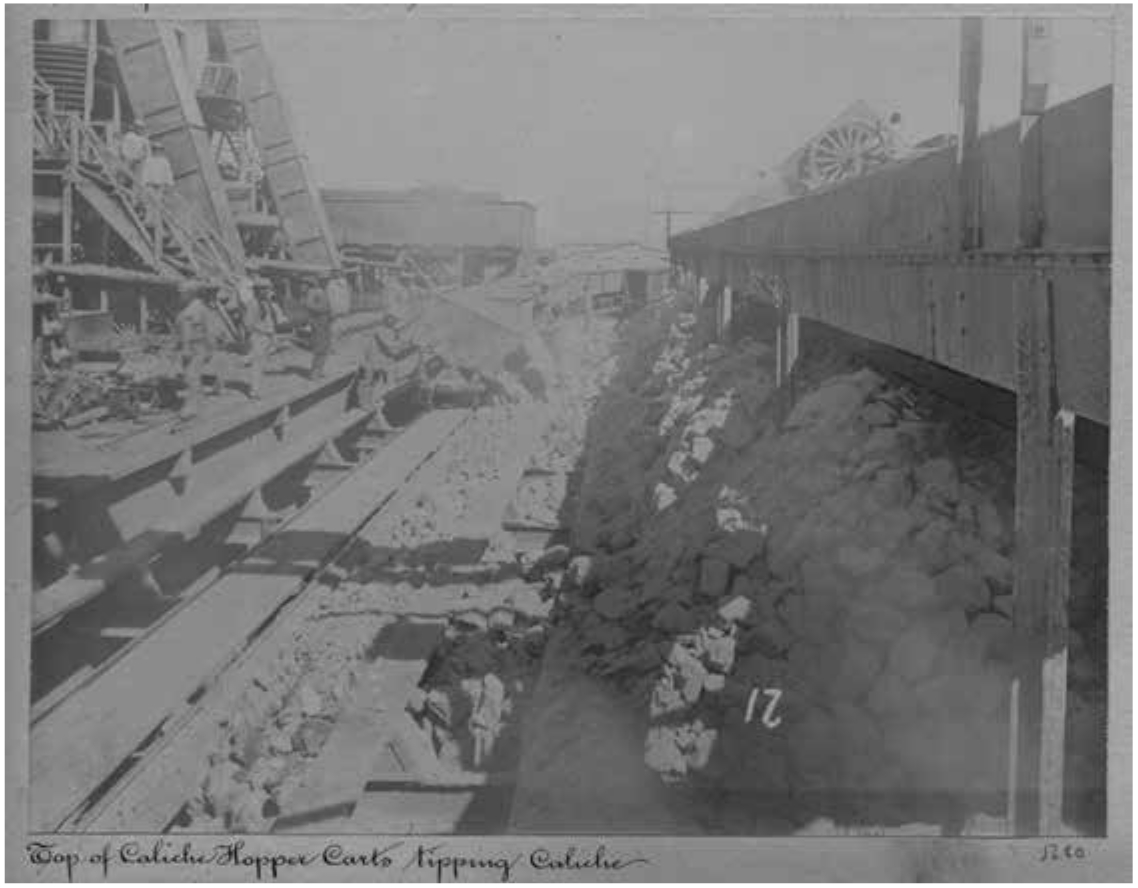

In the album, the desert landscape dominates (expansive ochre fields under large empty

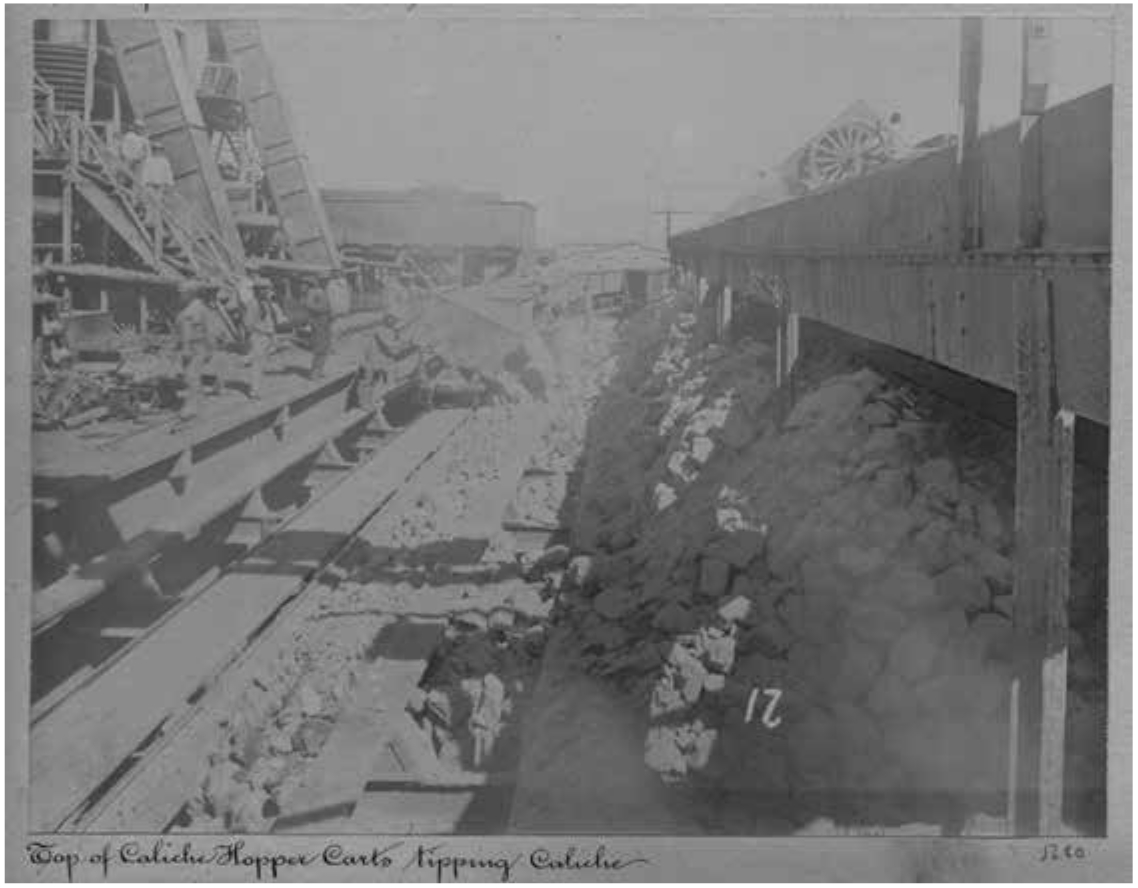

skies), until the arrival of technology. The album's seventeenth frame is a well-organised

image of industry (Fig. 15). The tracks, girders and planks (the railway carrying carts of caliche and regular openings of the crusher's hopper) extend from bottom left to centre providing

lines of perspective around which the image's elements are drawn into symmetry and

balance. Steep sided structures, exposed constructions reproducing metal forms, rise

on either side of the tracks. Industry lies between, represented by activity and quantity,

productivity, to use a term taken from Economics. Men engage in purposeful stances

within the industrial architecture and oversee mounds of materials. At the very centre

of the image, where lines of perspective converge, is its defining moment, a stage

for the industrial process' announced by the title: "Top of Caliche Hopper Carts tipping

Caliche." Three men reach and hold the cart as dusty rocks pour from the bottom and

spill from the top (Fig. 16). The foremost figure's face, whose leaning body is aligned with the cart to become

part of the shape and movement of the tipping caliche, is turned upwards towards the

camera. His glance punctures the image, alerting its viewers, us, that this moment

is being presented. But the image's other elements combine to encourage the dismissal

of his stare, and the challenge it implies, in favour of the documentary requirements

of nineteenth century industrial photography. The cart and its handlers might have

paused for the camera but the heavy loads stacked behind them ratify that the sight

of a tipping cart of caliche is routine in nitrate processing, in fact, it is repeated in the image: a dust cloud

pours from a mule drawn cart, positioned above right. The viewer can see enough to

assume that this happens often.

15.

“Top of Caliche Hopper Carts tipping Caliche,” in Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899, no. 17.

16.

“Top of Caliche Hopper Carts tipping Caliche,” detail. 110

These moments in the journey of nitrate are not merely a record of where the photographer

stood nor is the narrative of nitrate his invention. I am assuming the photographer

is male, though I do not know his name and have no other sign of his identity. Records

of him have unfortunately been lost or overlooked; his anonymity is an historical

accuracy of a kind. The photographer of Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 cannot be distinguished as an individual practitioner because his work reproduces

standard photographic forms of the late nineteenth century. The sequencing of images

was created through considerable careful editing, their numbering and renumbering

is discernible on some plates (Fig. 15), but the composition of the views of the desert landscape and nitrate industry dutifully

follows the conventions of late nineteenth century photographic practices. The extraordinary

spaces of the Atacama Desert are presented as an industrial scene, like other industrial

scenes. The desert is framed through the practice of industrial photography, which

was well established by the time the album was compiled in 1899. The historian of

the art of the engineer, Francis Pugh, states:

During the latter half of the nineteenth century industrial photography became one

of the principal means for recording and publicizing the achievements of British industry,

so that by 1900 there was hardly an industrial sector which did not make use of photography

in one form or another11

It was from the mid-nineteenth century on when photographers with some professional

status were commissioned by engineers or contractors, to produce photographic records

of large-scale industrial schemes. Typically, it was ambitious structural interventions

on landscapes that were documented, such as bridges or tunnels for railway lines.

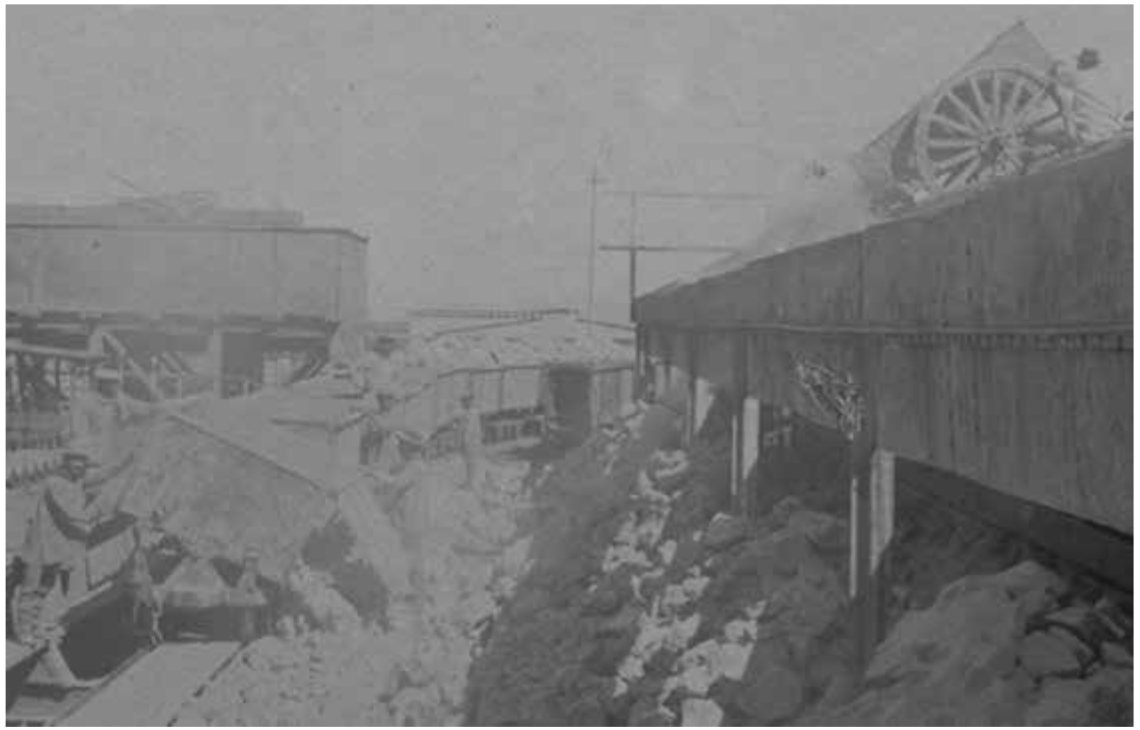

Henry Flather's Construction of the Metropolitan and District Railway (Fig. 17) is an important example of this photographic practice. Many of Flather's 64 images

contributed to the establishment of the conventions of industrial photography; I would

draw attention to just two images. One, Figure 17, is a perfectly arranged scene of industry. Flather deploys pictorial practices to

provide a frame through which industry can be represented; he organizes the view of

industry, brings order to the disorder of an unfinished industrial work. His photograph

has the formal arrangement of a landscape painting:12 a left to right, top to bottom axis creates movement across the picture plane. On

either side of this axis, the railway cutting across and the subject of the photograph;

alongside exposed surfaces of dark dug out earth and lighter rocky shelves lie heaps

of stuff, piles of wooden planks awaiting use, barrows of blocks ready to be carried

away. An unfinished scene is drawn into a balanced arrangement. A symmetry between

two cranes suggests an archway. The heaps of temporarily discarded stuff form geometrical

patterns, repeating rectangles or the lines of isosceles triangles. The incomplete

nature of the scene is busy but not chaotic; it is an image of the moment of material

transformation. Human figures hold a small part in this scene; they stand within its

industrial structures, as if emplacements, belittled by the amount of materials and

the scene's dimensions and scale.

17.

Henry Flather, The Construction of the Metropolitan District Railway, 1866, © Museum of London.

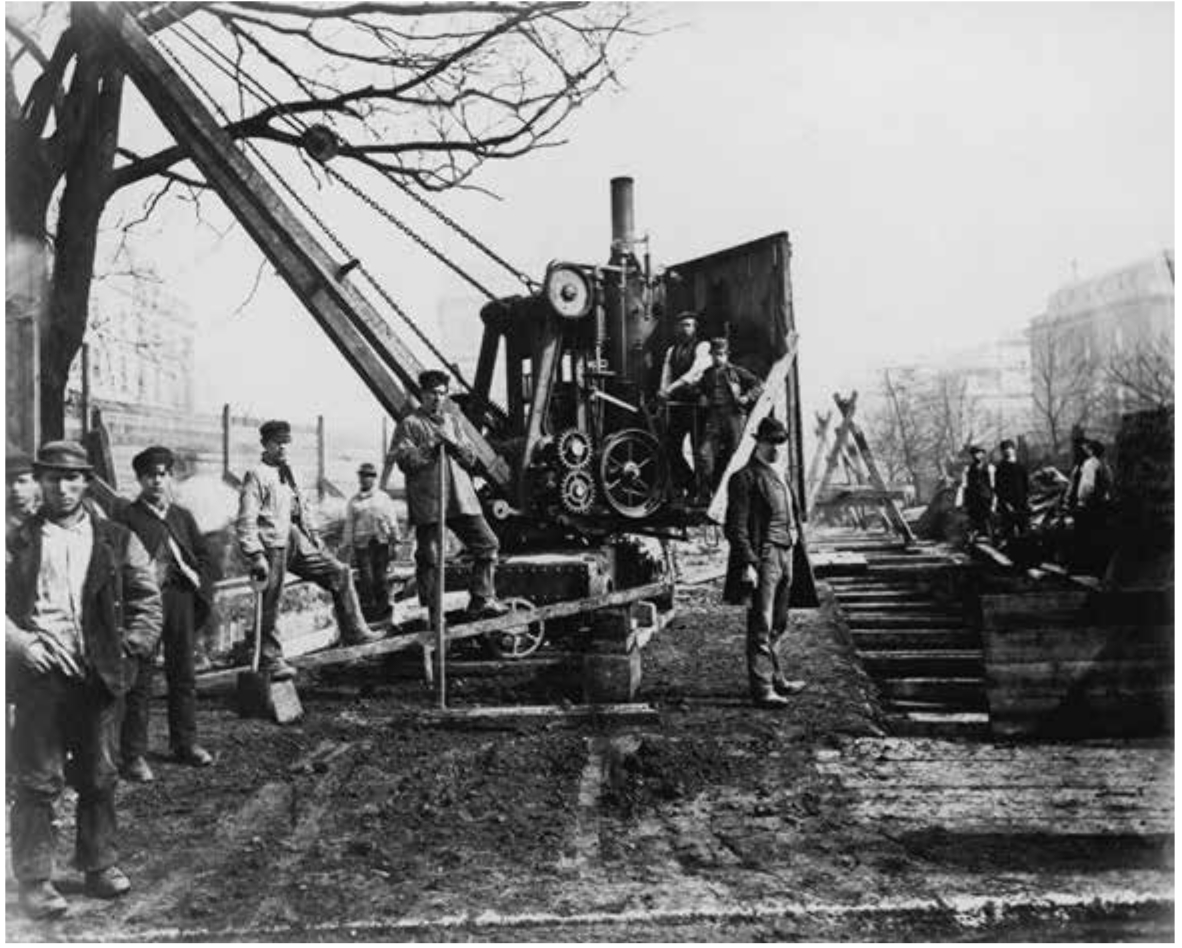

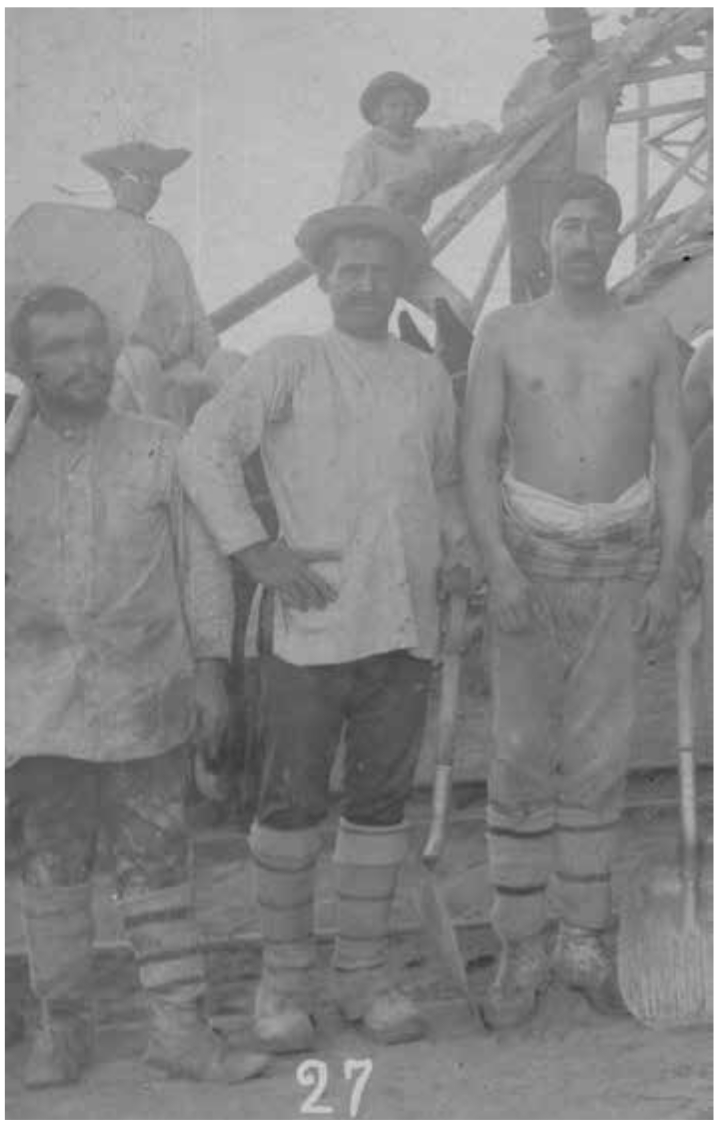

Another image of the Bayswater Excavations by Flather is captioned A gang of workmen around a steam crane which is removing spoil from an excavation

at Craven Hill (Fig. 18). It has the human figure, the worker's body, a group of laboring men, as its subject.

They are turned to face the photographer, the camera and, once the shapes of light

upon photographic plate are fixed in chemicals and reproduced, they face us, the photograph's

viewers. They have been positioned ascending and descending the steam crane, another

balanced classic painterly arrangement. The figures form sight lines from the left

and right that move towards the center of the image, to the pulley mechanisms, cogs

and wheels, the steam pipe atop it all, the pinnacle of the image. The group of laboring

men presents the technology of industrial work and themselves; the poses their bodies

hold can be read as industrial labor. The foreman positioned center right holds out

his chest and fills out his waistcoat to demonstrate his authority. The white jacketed

workers' stance, front leg bent, shovel held, back leg straight, does not simply display

his type of manual work but also his readiness to work. The group of laboring men

are not shown with their backs bent in labor (another trope of industrial photography).

We see they have stopped to be photographed, but labor is the photograph's subject,

as it is also represented in the Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique album's 27 image (Fig. 3).13

18.

Henry Flather, A gang of workmen around a steam crane which is removing spoil from an excavation

at Craven Hill, Bayswater Excavations, 1866-1868, © Museum of London.

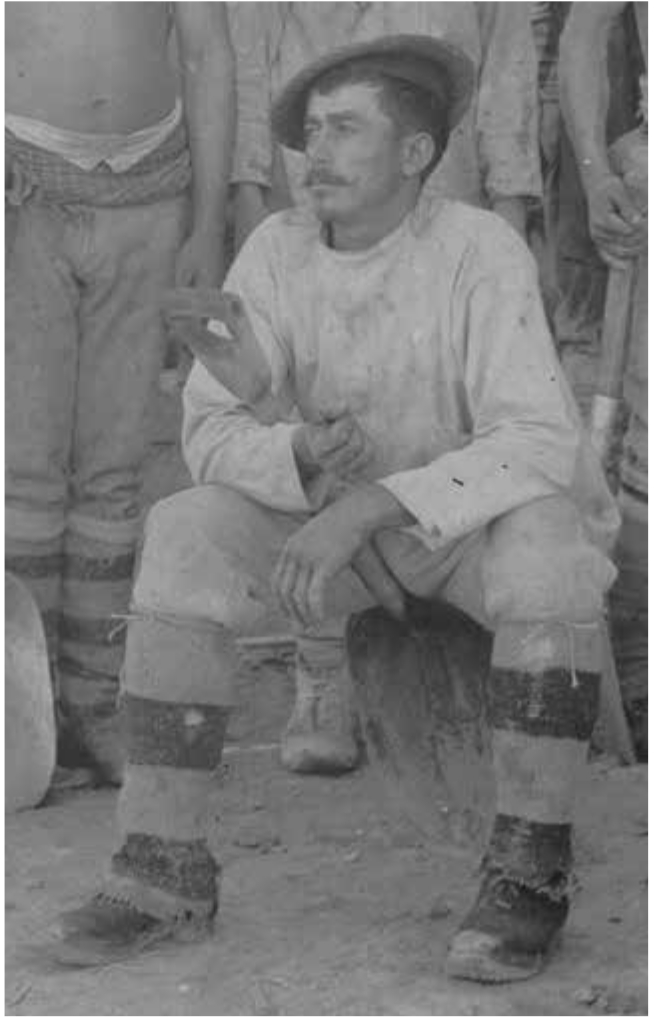

A row of nine nitrate workers confronts the viewer. They do so because they have been

lined up directly in front of the photographer and have held their positions. The

figure on the far left is posed as for an individual portrait: his gently angled body

weighted on his back foot, his face and glance tilted upwards, he carries a token

of his identity, the shovel (Fig. 19). The rest of the row of nitrate workers has simply faced the camera: a full-length

frontal view of their entire body is plainly visible: legs straight, arms to their

sides, faces looking forward. They appear to await a military inspection; nitrate

workers on display. Yet, they do not entirely present themselves. Their presentation

is arranged within the image, through the photograph's composition. The row of workers

is mediated by a single figure in the foreground (Fig. 20). Seated on his shovel, beneath eye level, he does not block out the view of the

nitrate workers; moreover, to use metaphors stemming from performance, he announces

them. In the background there are nine figures (Fig. 3). Their faces less distinct, their bodies partially visible, they fade into the image's

architecture. Five figures with the smaller frame of a child are evenly spaced ascending

wooden stairs, and function as supporting cast to the main players. Five of a row

of nine nitrate workers are bare-chested and four stand together in the middle. If

the row is the main performance; they are its centerpiece. All other nitrate workers

are fully clothed in every other image in the album. Desripiadores, those shoveling waste of nitrate processing from boiling tanks, worked with their

shirts off. One female North America observer, Mabel Loomis Todd, noted they were

half-naked.14 Perhaps, then, in a moment of rest from work prompted by the act of photography (the

interruption of their routine by the photographer's arrival, the installation and

adjustment of his equipment), some men cooled and dressed, or others felt the heat

of the day and undressed. Two white shirts hang over the wooden structures supporting

the Oficina's boiling tanks, the collar-less one, a worker's garment, just visible.

Unintentional or otherwise, this is a show of strength: physical, manual, masculine.

That much can be seen but its meaning is not clear, neither in 1899 nor now. Classical

and primitive subjects wear bare chests in all kinds of imagery from sculpture to

comic strips: ancient warriors and colonial peoples.

19.

"Group of Desripiadores," detail.

20.

“Group of Desripiadores,” detail.

To try to understand the contradictions of such a show of strength, I would like to

consider that moment of interruption, the act of photography. When the photographer

was ready to take his shot, did he fear asking the nitrate workers to appear fully

dressed? Or, did they reach for their shirts and he told them to stand for the photograph

without them? In that moment, to whom did their strength belong? There are two figures

who do not stare at the photographer or at his camera but look to their left: the

seated figure in the foreground and an upright figure parallel to him, behind the

row of nitrate workers. They seem to be looking at the same thing or the same person;

they wait for the photograph to be taken, the moment to pass, to then perhaps receive

a sign from the foreman, el capataz, to get back to work.

Like Flather's Bayswater Excavations photograph, the "Group of Desripiadores" is an

image of work arrested, but industrial labor is its subject. I am not arguing that

the photographer of Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique had seen Henry Flather's photographs or admired the work. My proposal is that by

1899, when he arranged his tripod on the uneven surface of the rocky desert to point

his heavy camera towards an empty landscape before turning to focus upon the operations

of machinery, a way of picturing industry was already in place. Furthermore, by the

1880s, according to Francis Pugh, photographic documentation of industrial works had

become part of that industrial work, organized by the engineer, contractor or company

carrying it out. At this time, he states "the engineer-photographer becomes a more

familiar figure."15 The photographer of the album is just another industrial worker,16 and the less we know about him, his relationship to the nitrate companies, the owners

of the machinery or the railway, the more the photographs appear to record the historical

inevitability of industry, that the desert was there just waiting to be industrialised,

rather than his own existence which was contingent upon industrial relationships.

Each industrial stage of nitrate mining at the Alianza Oficina documented in its album

was "entwined" with,17 even determined by, competitive relationships of accumulation of capital. If it is

not a contradiction in terms, nitrate trafficking was a matter of competing monopolies.

Following Chile's victory in the War of the Pacific over neighbours Peru and Bolivia,

the natural monopoly of sodium nitrate of the Atacama Desert became the site of concentrated

capitalist exploitation. Competition for concessions to mine nitrate fields and the

railway routes from these desert fields to the Pacific ports led to the rapid expansion

of nitrate mining and the industrialisation of the Atacama. One nitrate company, for

instance (that owned by Antony Gibbs, John Thomas North, Balfour Williamson, Campbell

Outram and Folsch Martin) worked several nitrate fields and owned the nitrate Oficina

and warehouse in Iquique or Pisagua where sacks of stored nitrate awaited export to

Liverpool, London and Europe. German farmers, who grew beets for cattle feed and liked

the quickening effect of nitrate fertilizers, were important customers. The railways

that transported nitrate from the desert to the sea were the "key" to profits and

profiteering in nitrate.18 Railway companies charged nitrate companies for transportation. Monopolies reigned.

High tariffs were charged per quintal (close to an American hundredweight) of nitrate.

In 1887, British engineer turned financial speculator John Thomas North, bought 7,000

shares in the Nitrate Railways Company, a Peruvian firm owned by the Montero brothers,

but registered in London in 1882. The following year, North became company director.

Herbert Gibbs complained to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that "the monopoly of

the nitrate railways was weighing unmercifully upon British capital invested in the

nitrate works."19 Gibbs' objection to paying North's high tariffs and, more broadly, to his parvenu

status in British nitrate trade, meant that the Alianza nitrate field remained unworked

as they diplomatically pressed for a concession to build their own railway line, and

until North's railway monopoly was brought to an end. Monopoly was the nature of the

nitrate business.

Allan Sekula states that industrial photography was the form of monopoly capitalism:

"institutionalized industrial photography characteristic of the epoch of monopoly

capitalism."20 Are the images that comprise the Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 album so bound to Antony Gibbs and Sons interest in Chile that they can only display

the values of the monopoly's capital? The album holds a dual status; it is both a

general and specific form. It is of a type, an example of industrial photography,

a generalizable representation of a landscape transformed by feats of engineering:

cuts, lines and movement made by massive metal structures and engines. But it is also

quite a specific representation of Antony Gibbs and Sons interests. I use interest here to evoke at least three of its meanings: a scene that might attract attention,

a matter of concern, and their business. Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 is an album of interest to Antony Gibbs for all these reasons. In Mr. Smail's words,

it is "a souvenir" of "our last but I hope not least among nitrate oficinas"; the

album Oficina Alianza brings a part of it into a London office. It is accepted as such. Photographic bounty

is analogous to profitability. "My dear Smail" replies Henry Hucks Gibbs:

I am much obliged to you for the excellent photography of the Alianza [...] handsome

volume [...] If the business itself produces a corresponding handsome result, it will

be in great measure due to your zeal and ability, which are fully appreciated by my

friends as well as by me.21

So where might the Benjaminian "spark of contingency" be found in "A Group of Desripiadores"?

It must be there since it is the only image of the album that has been widely reproduced.

It might be found in the nitrate workers' stance. Even without their shirts, they

guard themselves. Their bare chests, a display of physical and collective strength

for the photographer in Oficina Alianza in 1899, may be the spark. Quite out of chronological sequence, it illuminates the

gestures of the nitrate workers lined up in front of General Silva Renard's troops

in 1907. Micheal Monteon relates that when they surrounded the Escuela Santa Maria,

"Labourers greeted the soldiers' arrival with hoots; some ripped open their shifts

and dared the troops to fire."22 Or, the reality that has "seared the subject" is in the hands of a nitrate worker.

The sixth figure from the left holds his shovel with an easy familiarity: thumb balanced

on the top of the handle, fingers gently curling under it, resting but ready to hold

it more tightly (Fig. 21). At first glance, there appears to be a perfect fit between hand and tool. The repeated

act of shoveling, of laboring, can be seen in the image of physical familiarity. More

details can be detected between the hand and the tool, the nitrate worker and the

shovel: there is fabric wrapped around its handle. All visible shovel handles are

similarly wrapped. Nitrate workers' dress have a number of fabric bindings; some,

known locally as polainas, are bound around their waist and their socks to protect their skin from the abrasive

mined material of the desert: salty, sharp nitrate and dusty, dirty ripio. The nitrate worker's gentle grasp over the folds of fabric wrapped around his shovel's

handle reveals some of the hard labour performed in an inhospitable place. Thus, momentarily,

the material conditions of mining in the Atacama Desert are captured in the photograph

numbered 27 (Fig. 3) in The Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 album.

21.

"Group of Desripiadores," detail.

Conclusion

Despite the orderly sequences of productivity and profit revealed by this "album of

views" of the nitrate industry, I have been unable to suppress the "urge to search

[...] for a tiny spark of contingency." There is a tension between the album of industrial

photography and the photographs it contains, or at least one: "A Group of Desripiadores."

They pull in different directions to reveal nothing less than the historical contradictions

of industrial capitalism: pictured here is the inevitable opposition between mining

monopolists and the labor of miners. In the photographed bodies of the ripio workers, we can see both industrial oppression and organised resistance.

The Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 album is a document of industrial capitalism. Its long photographic sequence, which

begins with desert rocks and ends with bagged commodities, highlighting the dynamism

of machinery in this material and spatial transformation, is an account of industrial

progress. Its articulation is dependent upon the practice of industrial photography,

Alan Sekula's "characteristic" form of capitalist monopoly. The album Oficina Alianza and Port of Iquique 1899 reproduced a series of scenes of industry that were already established views: the

dramatically altered landscape, the force of machinery, the image of labour obediently

coming to a stop. Plate 27, "A Group of Desripiadores" (Fig. 3), is just another of those "characteristic" forms of industrial photography wherein

the workers' bodily strength stands as part of the documentation of the amassing of

capital. Pasted into the album, their image was transported from Iquique to London,

following the same path as the bountiful bags of nitrate and their detailed account

books, to be received as an analogy of profit: a "handsome volume" that projects a

"handsome result." In the photograph, capital assumes a visual rather than numerical

form. Yet "A Group of Desripiadores" has been retrieved from the hands of monopolist

merchant houses in London through the same process by which it advanced itself: photography.

It is a "dialectical image."23 The light of the Atacama Desert that filtered back through the lens of the camera

to react with the chemical covering of its plate left evidence of the reality of mining

in Chile: the abrasive conditions of shovelling nitrate residue overcome by the collective

strength of those who stood to face the camera and the forces that had brought them

all there. §